Original Research

Faces of Power in Organizations: Foundations, Applications, and Extension

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

Questions of power are core to organizations, organizing, and the conduct of the organized. Organizational research, however, often avoids addressing questions of power in the direct, explicit, straightforward fashion that their theoretical importance would warrant. Mainstream management and organization studies, including work and organizational psychology and organizational behavior, typically limit themselves to basic and narrow conceptualizations of episodic interpersonal power. Building on broader theorizing in political and social science, an integrative literature review has introduced the ‘four faces of power’ to organizational research a decade ago. Albeit frequently referred to, applications of this model seem rare. However, a systematic assessment of the literature is lacking. Against this backdrop, objectives of this contributions are three-fold: First, an overview of foundational theories and taxonomies for the study of power in organizations is provided. Secondly, a semi-systematic review of the uptake of the ‘four faces of power’ taxonomy in the organizational literature is presented. After seven identified applications are summarized, the current state of knowledge and further research needs are discussed. Finally, an extended version of ‘six faces of power’ is suggested. Envisioned is a perspective that puts power into the foreground of organizational research.

Faces of Power in Organizations: Foundations, Applications, and Extension

University of Innsbruck, Department of Psychology, Innsbruck, Austria

|

Abstract |

|

Questions of power are core to organizations, organizing, and the conduct of the organized. Organizational research, however, often avoids addressing questions of power in the direct, explicit, straightforward fashion that their theoretical importance would warrant. Mainstream management and organization studies, including work and organizational psychology and organizational behavior, typically limit themselves to basic and narrow conceptualizations of episodic interpersonal power. Building on broader theorizing in political and social science, an integrative literature review has introduced the ‘four faces of power’ to organizational research a decade ago. Albeit frequently referred to, applications of this model seem rare. However, a systematic assessment of the literature is lacking. Against this backdrop, objectives of this contributions are three-fold: First, an overview of foundational theories and taxonomies for the study of power in organizations is provided. Secondly, a semi-systematic review of the uptake of the ‘four faces of power’ taxonomy in the organizational literature is presented. After seven identified applications are summarized, the current state of knowledge and further research needs are discussed. Finally, an extended version of ‘six faces of power’ is suggested. Envisioned is a perspective that puts power into the foreground of organizational research. |

Keywords: Power in Organizations, Four Faces of Power, Coercion, Manipulation, Domination, Subjectification, Literature Review

Introduction

Power and control are core to the design of organizational structures, the processes of organizing, and the attitudes, experiences, and behavior of those who are being organized (Clegg, 2009; Mumby, 2015). The power perspective is indispensable to understand the socio-historical development and differentiation of workplace regimes (Hornung & Höge, 2021; Weiskopf & Loacker, 2006), evolving organizational structures, and corresponding paradigms of management (Barley & Kunda, 1992; Fleming, 2014; Omidi et al., 2023). Questions of power and control, thus, are at the heart of social science research into organizations and management – albeit not always dealt with in an explicit, direct, and straightforward way (Mumby, 2015). Despite its theoretical and practical centrality, power in organizations is a contested, controversial concept (van Baarle et al., 2024). This striking paradox is likely not independent from the observation that the powerful are typically not interested in discourses problematizing power, but prefer to normalize and naturalize the status quo in power relations as inevitable, rational, and without alternatives (Klikauer, 2019; Reed, 2012; Shatil, 2020). Based on the insight that power relations pervade all societal structures and discourses, it would be a folly to assume that research is exempt and free from interest-guided influences. Thus, it has been argued that psychological research in work and organizations, for instance, provides as much knowledge about workplace practices as it is a managerial ideology, that is, meaning in the service of power (Bal & Dóci, 2018; Hornung & Höge, 2024). A second reason for downplaying the role of power in organizations might be found in a strong motivation of humans to construe themselves as autonomous agents acting on their own free will, rather than being ‘pawns of power’ controlled by forces beyond their influence and comprehension (Knights & Willmott, 1985). In any case, power is a sensitive issue and its central role in shaping workplace attitudes and behaviors that are formally defined as ‘voluntary’, such as taking on additional tasks or working unpaid overtime hours, dynamics of leadership and teamwork, as well as organizational culture and socialization, for example, appear to be frequently overlooked or downplayed (Collinson, 2020; Greer et al., 2017; Tourish & Willmott, 2023). Pervasiveness and centrality of power renders it not one among many particular explanatory mechanisms, but rather a comprehensive perspective for understanding society, organizations, and social behavior (Clegg, 2009; Mumby, 2015). A number of conceptual articles have shown that applying a power perspective to topics where it has been previously neglected, for instance boundary spanning (Collien, 2021), leadership (Collinson, 2020), or political capital in organizations (Ocasio et al., 2020), can provide breakthrough insights with the potential to move the field forward. The above outlined considerations should suffice to illustrate, why paying more attention to power and control in organizations is warranted and of utmost theoretical and practical importance.

By taking stock and reviewing the literature on power in management and organization studies, this article seeks to contribute to a perspective that puts issues on power into the foreground. After some preliminary remarks on definitions of power, foundational theories taxonomies of power in organizational contexts are presented, based on a narrative literature review. Although far from comprehensive, to the best of the author’s knowledge, such a compilation of models of power does not exist so far. In the subsequent section, the results of a semi-systematic literature review are presented, exploring the uptake of the model of the ‘four faces of power’ (Fleming & Spicer, 2014) in the organizational literature. Altogether seven studies conceptually or empirically applying this taxonomy are identified and reviewed. In the final section, the current state of the literature as well as further research needs and opportunities regarding power in organizations are discussed. Lastly, a theory-based differentiated and extended version of ‘six faces of power’ is suggested to further advance the study of power in management and organizational research.

Foundations: Theories and taxonomies of power

Power is a complex and contentious topic. Thus, unsurprisingly, numerous definitions, taxonomies, and theories of power exist. Despite considerable variation, a widely accepted basic definition describes power as the ability of an actor or entity ‘A’ to get another entity ‘B’ to do something they would not otherwise do (Dahl, 1957; Knights & Willmott, 1985). While some definitions emphasize control over valued resources or punishments, others stress that power entails overcoming resistance (Elias, 2008) or that the induced effects are not in the interest of the target of influence (Clegg, 2009; Mumby, 2015). Based on an integration of previous conceptualizations, Sturm and Antonakis (2015) have defined interpersonal power in terms of discretion or agency to act as well as possession of the means (e.g., innate, position, resources) to enforce one’s will over others and/or one’s environment. More broadly, organizational power has been defined as the actions of any individual or institutional system that controls or influences the behavior or beliefs of (other) members of the organization (Lawrence & Robinson, 2007). Conceptualizations of power vary, depending on the breadth of the underlying perspective and level of analysis. Thus, different forms, modes or ‘faces’ of power have been differentiated. Based on a narrative review of the literature, the following section gives an overview of foundational theories and taxonomies for research on power in organizations. The focus is on taxonomies of power, rather than the associated theories, which tend to be more complex and can only be superficially sketched out. Table 1 summarizes nine theories and taxonomies for the study of power in organizations, outlined in more detail below.

Labor process theory

Rooted in the Marxist critique of the political economy, labor process theory offers a comprehensive socio-historical framework for analyzing power and control in organizations. Its basic assumption is that to solve the ‘transformation problem’ from acquired abstract labor power (time) into profitable performance, employers need to apply control (Braverman, 1974). The exercise of power can take on different forms from work contracts favoring employers (formal control) to direct coercion by supervisors and technology (real control), but has been increasingly analyzed as normative (or ideological) control through consent and commitment (Burawoy, 1982; Hornung & Höge, 2021). This historic development has been termed a shift from ‘despotic’ to ‘hegemonic’ workplace regimes (from Taylorism to modern human resource management), with hybrid forms of ‘hegemonic despotism’ (Vallas et al., 2022). In contrast to most organizational theories of power, labor process theory formulates an inherent conflict of interest between employees and employers (represented by management), as economic principles of capital accumulation though the extraction of surplus value tend to predispose systemic power towards demanding perpetual work intensification and/or labor cost reduction.

Table 1

Foundational theories and taxonomies for the study of power in organizations

|

Theory or taxonomy |

Brief description of core components |

Exemplary references |

|

Labor process theory |

Focus on power imbalances and conflicts of interest in employment; control needed to solve transformation problem from abstract labor time to profitable performance; control through contracts, coercion, and commitment. |

|

|

Organizational compliance theory |

Organizations are characterized by different compliance mechanisms based on coercive, remunerative or utilitarian, and normative power, resulting in corresponding attachment by members, labeled alienative, calculative, and moral involvement |

Etzioni (1975), |

|

Bases of social power theory |

Power as the potential to influence the behavior, beliefs or attitudes of another, based on reward, coercive, legitimate (right), expert (knowledge), referent (charisma), and informational (explication) power; perspectives of agents and targets of power |

Raven (2008), Elias (2008), Dirik and Eryılmaz, (2018) |

|

Structural and psychological power |

Structural or objective power of hierarchical status or position to control resources (e.g., pay) versus psychological or subjective sense of power as assessments of one’s ability to influence another person or to impact one’s environment more broadly |

Tost (2015), |

|

Episodic and systemic power |

Episodic power as discrete, deliberate, strategic attempts by actors to exercise influence on others; systemic power as embodied in social, cultural, bureaucratic, technological institutional structures, shaping ways of thinking and acting |

Lawrence et al. (2012), |

|

Three-dimensional view of power |

First dimension of power through unilateral decision-making; second dimension refers to non-decision making and agenda setting; third dimension as ideological domination to make targets adopt positions that run counter to their objective interests |

Lukes (2005; 2022), Clegg, 2009),

|

|

Power-over, power-to, and power-with |

Perspective of power-over-others complemented by power-to-act to achieve desired outcomes; co-active power-with-others as collective action; enabling power as empowering others to act may itself be a form of power-over-others to act in a certain way |

Pansardi and Bindi (2021), Abizadeh (2023), van Baarle et al. (2024) |

|

Disciplinary power and biopower |

Disciplinary power as embodied in institutionalized systems of standardization, surveillance, assessment, and sanctioning behavior; biopower as producing and mobilizing the appropriate individual as an autonomous and adaptable subject of power |

Weiskopf and Loacker (2006), Lilja and Vinthagen (2014), Fleming (2014) |

|

The four faces of power |

Integrative taxonomy distinguishing episodic coercion and manipulation and systemic domination and subjectification; sites of power as politics in, over, through, and against organizations; most differentiated model of power; focus of presented review |

Fleming and Spicer (2014) |

Labor process theory has a long tradition in analyzing power and control in organizations and has been continuously updated to integrate ongoing developments, such as the importance of immaterial and emotional labor, employee skills, and new forms of management and workplace regimes, such as platform work and algorithmic management. In a recent systematic review of the uptake of labor process theory in the field of critical human resource management, Omidi et al. (2023), identify institutional forces, control regimes, solidarity and resistance, and the deskilling-upskilling paradox as main themes of the growing literature.

Organizational compliance theory

Another rather early theory of power with an organizational focus was presented in the comparative macrosociology of organizations by Amitai Etzioni (1975). Accordingly, different types of organizations can be characterized by specific compliance mechanisms, categorized as coercive, remunerative or utilitarian, and normative power, resulting in corresponding forms of attachment by lower-level members, labeled alienative, calculative, and moral involvement (Dodge, 2016). Coercive power, seen as characteristic for prisons and military organizations, is based on the use of force and physical sanctions (e.g., violence, deprivation), resulting in reluctant compliance and a high-intensity negative involvement based on alienation. Utilitarian or remunerative power operates with extrinsic rewards (e.g., pay and privileges), stimulating an instrumental orientation, seen as characteristic for gainful employment. Lastly, normative power, based on symbolic or intrinsic rewards (e.g., status, meaning), was initially seen as prototypical for churches or schools, prompting high-intensive positive moral involvement by lower-level organizational members. Originally formulated as ideal-types, subsequent research in employment contexts has established that work organizations typically use of mix of coercive, remunerative, and normative power, resulting in complex and hybrid forms of employee involvement (Azim & Boseman, 1975). Based on Etzioni’s theory, a self-report scale of organizational commitment was developed by Penley and Gould (1988), but, with few exceptions (Hornung, 2010), seems to be rarely used.

Bases of social power theory

Established in social psychology is the bases of power taxonomy by French and Raven (Elias, 2008; Raven, 2008). Power is conceptualized as the potential to influence the behavior, beliefs or attitudes of another. Distinguished are reward power (compensation), coercive power (punishment), legitimate power (right), expert power (knowledge), and referent power (identification). Later, informational power (explication) was added as a sixth base for eliciting compliance. Subsequent research has elaborated these bases (Elias, 2008). Impersonal and personal aspects of reward and coercive power were distinguished; position, reciprocity, equity, and dependence were specified as bases of legitimate power; further, positive (compliance) and negative (reactance) responses to expert and referent power as well as direct and indirect use informational power were differentiated. Bases of power are variously discussed from the perspective of agents or targets of power. The suggested power/interaction model more clearly adopts the perspective of agents of power, including the motivation to influence, assessment and choices of power bases, and consideration of effects, such as compliance or resistance by the other party (Raven, 2008). The bases of power taxonomy has been widely received and applied to numerous contexts, particularly, with regard to leadership (Dirik & Eryılmaz, 2018; Carson et al., 1993). Nonetheless, applications in current organizational research are rare. An exception is the study by Peiró and Meliá (2003), distinguishing between formal (legitimate, reward, punishment) and informal (expert, referent) power and establishing distinct properties for each of these higher-order factors. Among others, these authors show a correspondence between formal and objective power based on hierarchical status, the use of which is perceived as coercive by the targets of power, whereas informal power is reciprocal and relates negatively to social conflicts. This approach, thus, appears useful for examining different qualities of power and processes of social influence at the interpersonal level.

Structural and psychological power

Frequently distinguished are structural or objective power and psychological, subjective, or sense of power (Tost, 2015). Objective power is often equated with structural (or positional) power, as possession of hierarchical status or rank associated with demonstrable control over resources (e.g., pay and personnel decisions), however, also comprises situational or relative positional power in interacting with other individuals with higher, equal or lower standing in the hierarchy (Heller et al., 2023). Psychological power typically refers to subjective assessments of one’s ability to influence another person in a given situation, but also includes perceived competence, autonomy, and independence to impact one’s environment more broadly. The former is referred to as interpersonal, the latter as personal power. These two types of ‘state power’ are assumed to be influenced by psychological ‘trait power’, that is, individual differences in generalized self-efficacy regarding one’s ability to be in charge and exercise control (Heller et al., 2023). Research has elaborated how objective (structural) power translates into subjective (psychological) power and how, in this process, responsible or benevolent modes of power use can be activated (Tost, 2015; Tost & Johnson, 2019). In general, however, extensive research across multiple domains has established that the default mode of interpersonal power manifests in self-serving or agentic behaviors and instrumentalization or objectification of others in pursuit of own interests and goals (Foulk et al., 2020). Notably, these antisocial negative consequences are particularly pronounced for objective structural or position power, whereas, apparently, psychological sense of power can also be construed in a benevolent or responsible manner, depending on individual differences, contextual factors, and psychological processes. However, this seems to be the exception rather than the norm.

Episodic and systemic power

An important distinction established in the literature is the one between episodic and systemic power (Hekkala et al., 2022). Accordingly, episodic power refers to discrete, deliberate or strategic attempts by actors to directly exercise influence on others via different means. Thus, episodic power largely corresponds with the interpersonal perspective on power. In contrast, the notion of systemic power emphasizes modes of influence that are manifested and embodied in social, cultural, bureaucratic, and technological institutional structures, tacitly shaping ongoing practices and routine ways of thinking and acting (Foldy & Ospina, 2023). Systemic power is less direct and observable only from a broader perspective that transcends the respective socio-cultural and institutional frame of reference. Mainstream organizational research typically tends to focus on more narrow conceptualizations of episodic power, whereas consideration of systemic power is characteristic for socio-critical approaches in the tradition of the critique of ideology as well as for poststructuralist theorizing (Clegg, 2009; Seeck et al., 2020). In practice as well as in theory, however, the episodic-systemic distinction is not completely clear-cut as episodes of power use are embedded in and, on aggregate, are constitutive for overarching systems of power. For instance, one notable study on radical change processes in professional service firms (Lawrence et al., 2012) has examined how episodic and systemic power interact and reinforce or collide with each other to either facilitate or impede organizational transformations. A noteworthy elaboration of how episodic and systemic power influence cognitive processes of sensemaking was provided by Schildt et al. (2020) and was extended by Vaara and Whittle (2022) to collective sensemaking with a focus on systemic power. Overall, it seems clear that focusing only on episodic and neglecting systemic manifestation provides not only an incomplete, but even a distorted view of power.

Three-dimensional view of power

Based on political and social theory, the three-dimensional view of power by Steven Lukes (Lukes, 2005; 2022) has been increasingly influential in organizational research (Clegg, 2009). Accordingly, power is exercised in the three ways. The first dimension is the most direct and visible form of power through unilateral decision-making and imposing the consequences on the other party. The second dimension is more subtle and refers to non-decision making. Also described as agenda setting, this form of power prevents inconvenient issues from being discussed, decisions from being made, and courses of action from being taken. Typically happening in secrecy or behind closed doors, this form of power is less visible and is discernable only in the suppression or absence of certain discourses or actions (e.g., censorship). The third and most radical dimension of ideological domination captures power to influence and shape public perceptions and preferences, making targets adopt positions that run counter to their objective social interests – a phenomenon that has long been discussed in critical social theory as the ‘false consciousness’ of hegemonic indoctrination (Augoustinos, 1999; Jost, 1995). There has been some debate in the political science literature as to whether a fourth dimension should be distinguished based on post-structural conceptions of governmentality as the systematic (pre-)formation of psychological structures (Digeser, 1992). Lukes (2022) himself, however, has rejected this notion. The taxonomy of the ‘four faces of power’ in organizational science (Fleming & Spicer, 2014), which has strongly drawn on Lukes’ theorizing, has incorporated such a fourth dimension (see below). Formulated from the perspective of political and social theory, the three-dimensional view of power is more oriented towards macro-level phenomena, but does not explicitly include a distinction between episodic and systemic power. However, at least the third dimension is clearly a form of systemic power.

Disciplinary power and biopower

The distinction between disciplinary power and biopower is rooted in the influential socio-historical works of Michel Foucault (Haugaard, 2022; Lilja & Vinthagen, 2014). Associated with the emergence of the ‘modern’ (i.e., post-medieval) European state is a third form of sovereign power, referring to the arbitrary and unconditional monopoly of law, judgment, and violent punishment by absolutist feudal rules. In contrast, disciplinary power is traced back to early capitalism and refers to the establishment of an institutional bureaucratic and technological order (the ‘disciplinary apparatus’) that prescribes, norms, and sanctions behavior, including education and training, examination and surveillance, as well as rewards for compliance and measured disciplinary actions for nonconformity. Whereas, in organizational contexts, sovereign power corresponds with forms of unfree, coerced and violently exploited labor, the ascent of disciplinary power is seen in as exemplified in the tightly controlled mass production regimes of Taylorism and Fordism, culminating in modern formalized hierarchical organizations and human resource management systems (Hornung & Höge, 2021; Weiskopf & Loacker, 2006). The concept of biopower, tied to the neoliberal turn in advanced capitalist societies, describes the biopolitical governance of populations regarding core aspects of life, health, reproduction, and effectiveness of societies as a whole, including discourses that intentionally shape their member’s mindsets, needs, and aspirations (Lilja & Vinthagen, 2014). The latter aspect of formative power and internalized control is inherent in the concept of neoliberal ‘governmentality’, which has also been taken up in the organizational literature (Munro, 2012; McKinlay et al., 2012). Weiskopf and Loacker (2006) were among the first to systematically analyze the shift from disciplinary to post-disciplinary workplace regimes as a change from attempts to constrain, divide, prescribe, and surveille to ensure compliance, towards using market-based management methods for producing and mobilizing the appropriate individual as an autonomous and adaptable subject. Today, using the labels of biopower, biopolitical organization, and biocracy (Fleming, 2014; 2022; Moisander et al., 2018), a growing body of studies focuses on similar advanced forms of organizational control through responsibilization and economic valorization (exploitation) of human life abilities and extra-work qualities, such as emotions, relationships, creativity and personal time and effort.

Power-over, power-to, and power-with

More recently, several authors have argued that the perspective of having ‘power-over others’ needs to be complemented by the ‘power-to act’ to achieve desired goals or outcomes (Abizadeh, 2023; Murt, 2020; Pansardi & Bindi, 2021). This distinction bears some semblance with the one between interpersonal and personal power (Heller et al., 2023). The idea is that power is not a zero-sum game involving limited resources, where the power of one party necessarily limits or restricts another party. Additionally, co-active power or ‘power-with-others’ is seen as emerging from relationships, agency, and collective action (Carlsen et al., 2020). In line with this perspective, resistance to power can be seen as a form of power in itself. From a more top-down perspective, van Baarle et al. (2024) have introduced the concept of enabling power as the use of (positional) power-over-others to increase the power-to-act of other organizational members, closely corresponding with notions of empowerment. Based on an integrative literature review, these authors identify actions, social mechanisms, and outcomes of enabling power. Tellingly, however, institutional and systemic conditions are explicitly excluded from their review, i.e., questions as to why power is unevenly distributed in organizations or why power-holders should be interested (or not) to increase the power of others, remain unaddressed. Thus, these authors try to focus on episodic power without considering the systemic power structures that these episodes are embedded in. A critical evaluation of the managerial discourse on empowerment is provided by Ivanova and von Scheve (2020). Drawing on labor process theory to conduct a discourse analysis of the practice-oriented management literature, these authors conclude that empowerment primarily reflects a management technique to reduce labor costs and increase responsiveness to market dynamics, accompanied by organizational delayering, downsizing, outsourcing, and work intensification. Accordingly, rather than a genuine transfer of power, empowerment is often more accurately represented as a managerial control strategy to cope with cost pressures, acceleration, and uncertainty. Thus, the allegedly enabling power-to-act may be a concealed form of power-over, enabling others only to act in prescribed ways, desired by the structural powerholders.

Based on an integrative review of the literature, renown critical management scholars, Fleming and Spicer (2014), have introduced the taxonomy of the ‘four faces of power’ to organizational research about a decade ago. Roughly corresponding with the first two dimensions by Lukes (2005), the two distinguished types of episodic power are coercion and manipulation, where the former refers to the direct exercise of control (e.g., decision-making, punishment, rewards) and the latter to more subtle attempts to ensure that actions and discussion remain within accepted predetermined boundaries (e.g., manipulation of rules, agenda setting, mobilization of bias). Following previous suggestions, based on the Foucauldian concepts of governmentality and biopower, Lukes’ (2005) third dimension was split up into domination and subjectification as two distinct forms of systemic power (Digeser, 1992). Domination refers to ideological indoctrination and sublimation of power relations as inevitable and natural, suppressing conflict and manufacturing consent (Burawoy, 1982). Subjectification more directly targets the sense of self, emotions, experiences, and identity construction of individuals (Weiskopf & Loacker, 2006). Reflecting poststructuralist theorizing on biopower and neoliberal governmentality, i.e., the governance through shaping mental states, subjectification refers to attempts to create the ‘appropriate individual’ (i.e., the ‘subject’ of power) that ‘wants’ to do what they ‘ought’ to do for the system to function efficiently (Alvesson & Willmott, 2002; Foster, 2017). Paradoxically, in this advanced form, the concept of power has evolved to take on a different meaning, such that it is introjected or embodied in the targets of power themselves (Hornung et al., 2022; McKinlay et al., 2012). Overall, the ‘four faces of power’ reflect a synthesis of the theories and taxonomies of power reviewed above, applied to organizational contexts. In addition to the four modes of power, the authors distinguish four sites of power with regard to politics in, over, through, and against organizations, structuring and compiling the literature within the resulting matrix (Fleming & Spicer, 2014). In the category of politics against organizations (e.g., by social movements), the four faces do not apply to power-over organizational members, but to the power-to engage in acts of resistance, such as protests and civil disobedience against the power of corporations. Integrating much of the previous literature, the ‘four faces of power’ taxonomy has become quite influential and is widely cited in management and organization studies. Beyond its intuitive appeal and integrating contribution, however, the theoretical and empirical usefulness of the model has not been systematically examined.

Literature review: Applications of the ‘four faces of power’

To assess the uptake ‘four faces of power’, as the most comprehensive taxonomy in organizational research, a semi-systematic literature review of its existing applications was conducted (Snyder, 2019). Suited to broadly and openly explore the literature, the semi-systematic review involves extensive searches, but without strictly following an a priori specified protocol. The focus was on English-language journal articles. To be included, articles had to fulfill the criteria of conceptually or empirically applying the complete four-dimensional model to issues of power within organizations. Excluded were contributions that only mentioned or reviewed the taxonomy, applied only parts (e.g., episodic versus systemic power; Foldy & Ospina, 2023; Schildt et al., 2020) or referred to other sites of power (e.g., between organizations; Hurni et al., 2022). According to Google Scholar, the original article by Fleming and Spicer (2014) had been cited more than 500 times (overall: 584; Web of Science: 251). All citing sources were screened for relevance based on titles and abstracts. Additional searches were conducted using different versions of the name of the model and combining the labels of all four faces. Thus, several hundred additional articles were screened. Eventually, seven articles were identified, one of which (Lawrence & Robinson, 2007) was published before the focal contribution by Fleming and Spicer (2014) and draws on an alternative, yet closely related four-dimensional taxonomy. After extensive additional searches and citation tracking, it was concluded that compiled articles likely constitute the full body of currently available applications of the focal taxonomy published in English-language journals. The seven articles are listed in Table 2 (in a didactically suitable order) and are summarized in the following.

Reviewed articles applying the ‘four faces of power’ in organizations

|

# |

Article reference |

Type |

Cited1 |

|

1 |

Berti, M., & Simpson, A. V. (2021). The dark side of organizational paradoxes: The dynamics of disempowerment. Academy of Management Review, 46(2), 252-274. |

Conceptual analysis |

182 (76) |

|

2 |

Langer, S. (2023). The relation of standards and power in management and organization research: Core notions and alternative avenues. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(4), 647-665. |

Narrative literature review |

1 (0) |

|

3 |

Lawrence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2007). Ain't misbehavin: Workplace deviance as organizational resistance. Journal of Management, 33(3), |

Conceptual analysis |

579 (203) |

|

4 |

Wilmot, N. V. (2017). Language and the faces of power: A theoretical approach. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 17(1), |

Narrative literature review |

38 (17) |

|

5 |

Schirmer, F., & Geithner, S. (2018). Power relations in organizational change: An activity-theoretic perspective. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 14(1), 9-32. |

Conceptual analysis, case study |

31 (11) |

|

6 |

Winkler-Titus, N. V., & Crafford, A. (2022). Resistance: Faces of power and how identity is reflected. South African Journal of Business Management 53(1), a3089. |

Case study |

2 (0) |

|

7 |

Alvesson, M., & Spicer, A. (2016). (Un) Conditional surrender? Why do professionals willingly comply with managerialism. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(1), 29-45 |

Conceptual analysis |

263 (124) |

Note. 1Overall citations according to Google Scholar as of August 2024, Web of Science citations in parenthesis.

Power and organizational paradox (article 1)

In an influential conceptual contribution, published in a high-ranking management journal, Berti and Simpson (2021) integrate the four faces of power with the literature on organizational paradoxes in strategic management. Paradox theory posits that organizing inherently involves persistent and interdependent tensions and contradictions that need to be overcome or resolved to transform the underlying conflicts into productive forces (Hargrave & Van de Ven, 2017; Glaser et al., 2019). Noting that this literature neglects power dynamics, the authors develop a theory of pragmatic paradoxes based on power relationships that impose incongruent demands on employees and prohibit them from finding adequate responses to these dilemmas. Accordingly, contradictory coercive power acts by the organization result in psychological double binds, whereas the manipulation of possible outcomes can lead to paradoxical predictions regarding outcomes. Imposing incompatible hegemonic values through systemic domination is linked to absurd phenomena, like ‘Kafkaesque organizations’ and ‘catch-22’. Attempts to shape employees’ identities via subjectification are associated with dissonant cognitions, resembling ‘Orwellian doublethink’. Detailing the disempowering psychological effects of each of these situations (e.g., blocking actions, delegitimizing questioning, reducing practicable strategies, self-censoring), the authors develop suggestions for overcoming pathological paradoxes of power through planned reforming strategies and emergent disrupting transformation. Overall, this article presents the most comprehensive approach so far to integrate the four faces of power into organizational theory with important implications for psychological research on work stressors arising from conflicting demands.

Power and standardization (article 2)

A recent narrative literature review by Langer (2023) explores interconnections between the four faces of power and the literature on standardization in organizations. Standards are understood broadly as social rules governing a variety of issues, such as quality management, industrial and consumer products, corporate social responsibility, or environmental management. In establishing and enforcing standards, power is seen as a central, albeit often neglected issue. Based on the conceptual distinction between design mode (establishing standards) and use mode (adherence to standards), coupled with the four faces of power, the article organizes the literature along six power-related notions of standardization. These refer to standard setting as an organizational strategy to control the environment (coercion), as battles for establishing standards (manipulation), and as the (re)production of discourses (domination). Standard use is framed as a chance for control as well as emancipation (coercion), as an outcome of institutional pressures (domination), and as self-regulation (subjectification). For the remaining two cases, subjectification in the design mode and manipulation is the use mode of standards, no examples were found in the literature. Overall, the article emphasizes the important role of power as a resource for designing and enforcing standards, but also as a consequence of institutionalized standards, as well as the disempowering effects of power asymmetries as an outcome of standardization. Further, the article suggests to explore the dialectics of standardization in the context of power struggles and the dynamic interplay between the powerful and powerless. Note that power in this review is conceptualized not exclusively as a restrictive and constraining force, but can take on facilitative and enabling forms, for instance, with regard to establishing and ensuring adherence to protective standards.

Power and workplace deviance (article 3)

The conceptual contribution by Lawrence and Robinson (2007) is based on an independent yet closely related version of the four faces of power. In this model, the episodic–systemic dimension is complemented with one of objectification–subjectification, that is, individual agency of the target is irrelevant versus assumed. This results in four modes of power, namely force (corresponds with coercion; e.g., restraint, punishment), influence (corresponds with manipulation; e.g., agenda setting), domination (e.g., material technologies, systemic discrimination), and discipline (corresponds with subjectification; e.g., surveillance, examination). Presented is a process model whereby organizational power use potentially (partly depending on the needs of the target) results in loss of individual autonomy, threats to positive identify or perceived injustice, thus, triggering frustration and mobilizing resistance in the form of workplace deviance. The latter is conceptualized in a corresponding four-dimensional taxonomy of more versus less serious and interpersonally-directed versus organizationally-directed acts. That is, personal aggression (e.g., sexual harassment, physical assaults), property deviance (e.g., theft, sabotage), political deviance (e.g., rumors, favoritism), and production deviance (e.g., absenteeism, withholding effort). Episodic power is linked to interpersonally-directed, systemic power to organizationally-directed deviance, while treating targets as objects is theorized to result in more serious violations than treating targets as subjects. This contribution is exceptional in framing counterproductive work behavior as resistance to organizational power – an explanation which is typically neglected in the mainstream literature (Liao et al., 2021; Schilbach et al., 2020). Theoretical differences with regard to the taxonomy of the four faces of power are evident, specifically, in the dimension of discipline, which does not fully capture the governmentality aspects of subjectification.

Power and corporate language policies (article 4)

Based on a narrative literature review and conceptual integration, the article by Wilmot (2017) synthesizes the language-sensitive literature in international management and organization studies along the four faces of power. The adoption of language policies, specifically, the ‘Englishization’ within multi-national corporations and between international businesses, is analyzed in terms of power use and corresponding forms of employee resistance are explored. Accordingly, episodes of coercive power obligating employees to use a particular language, are often met with refusal by native speakers of other languages. Episodes of manipulation arise when language policies are presented as legitimate and obvious, potentially triggering employee voice demanding to have a say in the underlying decision-making processes. Systemic domination applies to the hegemonic adoption of (English as) a corporate language in all written and verbal communication, including having native speakers lead meetings and conversations. This form of dominating power is potentially countered by employees trying to escape through disengagement or disidentification from the company. Lastly, subjectification refers to attempts to make employees voluntarily adopt the desired language to increase their status, legitimacy, and career prospects. A discussed form of resistance to subjectification is creation, which means that employees may invent novel and hybrid varieties of language use to uphold their cultural identity (Wilmot, 2017). Similar to the previous article, a contribution of this analysis is that corresponding forms of resistance are discussed with regard to each form of power, albeit in the quite specific context of corporate language policies.

Power in organizational learning and change (article 5)

The study by Schirmer and Geithner (2018) sets out to discuss the role of the four faces of power in the context of organizational learning and change. Drawing on cultural-historical activity theory, the authors conceptualize expansive learning in terms of both emergent relationships within or between groups (inclusion) and emergent activities (interpretation). Emphasizing contradictions and tensions, restrictive or preventive (e.g., exclusion and control) versus productive or facilitative uses of power are theorized about. It is concluded that episodic forms of power can be used to constrain expansive learning, but also to support it, especially when used by non-managerial actors. In this context, coercion can take the form of control over resources as well as resistance or spontaneous action, whereas manipulation of conflict not only serves to suppress dissent, but also to build shared mental models and reduce paralyzing uncertainty. In contrast, systemic domination is likely to function to uphold the status quo and, thus, to stifle expansive processes of inclusion or interpretation. Ambiguous effects are attributed to subjectification, which is assumed to enhance the potential ability to engage in expansive learning, but also to restrict willingness to question established standards. This theorizing is then applied to the case study of a bio-technology company, emphasizing power dynamics between different managerial and non-managerial stakeholders within the company. Empirical support for the theorized productive or enabling and restrictive or constraining effects of the different forms of power for expansive learning (including relationships and interpreting activities) is discussed. Further research has continued this stream, but has focused primarily on contrasting episodic versus systemic forms of power in organizational change (Lémonie et al., 2021), rather than applying the full taxonomy of the four faces.

Episodic resistance against systemic power (article 6)

In a case study of an organizational conflict in an institution of higher education in South Africa, the four faces of power are empirically applied by Winkler-Titus and Crafford (2022). Based on document analyses (e.g., contracts and agreements, websites, social media, newspaper articles) and interviews with various stakeholders (e.g., managers, employees, students) in the context of a discriminatory change in employment practices in a university setting, specific uses of power by different actors are identified and analyzed. Accordingly, systemic domination was used by management in a top-down fashion, constraining workers through disempowering and marginalizing work contracts and employment practices. Systemic subjectification was analyzed to be present, such that the most disadvantaged group of outsourced lecturers remained passive and paralyzed in light of the conflict, internalizing a subordinated, subservient professional identity, described as the experience of ‘modern slavery’. Episodic forms of power were analyzed predominantly as resistance by the groups of contracted employees and students against systemic managerial power. These episodic power acts included protests and direct pressure (coercion) via the organization and virtual mobilization of protesting employees, trying to force a management decision by instrumentalizing reputational threat to the institution. Protesting students engaged in more subtle agenda setting (manipulation) in the form of showing solidarity with protesting employees and reframing public perceptions of the professional identities of university staff as well as interpretations of the conflict in the public opinion. Overall, this case study illustrates the potential of the four faces as a useful theoretical framework to empirically analyze power struggles in workplace conflicts in practice.

Power and compliance in academia (article 7)

The final article by Alvesson and Spicer (2016) self-reflexively applies the four faces of power to the question why academics, business school scholars in particular, willingly surrender their autonomy and independence to comply with the managerialization and neoliberalization of universities and research in general (Fleming, 2022). Erosion of professional autonomy is exposed in the increasingly all-encompassing governance through publication metrics, journal rankings, performance evaluations, highly competitive career paths, and precarious employment. Faces of power are analyzed as complementing and reinforcing each other in multiple ways. Coercion is exercised through a burgeoning academic bureaucracy, powerful deans and administrators, and quantitative controlling systems, including rewards (e.g., incentives, promotions) and punishments (e.g., demotions, layoffs). Manipulation manifests in formal and informal agenda setting, prioritizing and promoting a specific type of research, and focusing on formalities of grants and journal publications without considering content. Domination proliferates certain professional norms and values, feeding a culture of so-called ‘excellence’ and emphasizing grandiosity of ‘star researchers’. Subjectification is seen at work in shaping the identities of academics themselves, for instance, internalizing publication metrics as a measure of self-worth and legitimacy. Moreover, it is analyzed how these four facets of power effectively reinforce each other, although many academics are critical of the described developments. Oscillating between outward compliance and personal resistance, results in paradoxical situations and double-think, often rationalized as ‘playing the game’ to survive and get ahead within a system perceived as dysfunctional yet inescapable and, thus, constantly reproduced. The faces of power also played a role in the single case study of a university lecturer by Alvesson and Szkudlarek (2021) on the erosion of resistance to academic managerialism. However, this application was not sufficiently developed to warrant inclusion in this review.

Discussion

This objective of this article is to provide an overview on power in organizational research. In light of this broad topic, such an attempt must remain incomplete and superficial. Nonetheless, hopefully, it can provide scholars with various starting points and differentiated perspectives for complexifying their theorizing and research with regard to power – not only acknowledging its coercive episodic forms, but also considering more subtle, manipulative and systemic manifestations. After summarizing important taxonomies and theories of power in the first part, the second part of the article focused on the most recent, differentiated model of the ‘four faces of power’ in organizations. Results of a semi-systematic literature review illustrate the breadth and potential of conceptual and empirical applications of his taxonomy. The majority of the identified journal articles (four out of seven) were conceptual analyses, two were based on narrative literature reviews, two presented case studies, and most included at least some empirical material for illustration purposes. Listed in Table 2 are also the citation counts of all articles. Although these numbers should not be overinterpreted, as they are strongly dependent on the publication date, the most influential articles are those dealing with workplace deviance (article 3), compliance in academia (article 7), and organizational paradoxes (article 1).

Despite the heterogeneity of topics and approaches, some common themes emerge. One is the association between power and contradictory tensions or paradoxes in organizations, addressed most explicitly in the first and the last contribution (articles 1 and 7). Being subjected to power creates oppositional and antagonistic material and psychological forces. These tensions become increasingly interiorized or introjected with more intrusive forms of control, ranging from unwilling and reluctant compliance to cognitive dissonance and paradoxical doublethink. A second recurring theme is the connection between power and resistance, resulting in attempts to conceptually match the faces of power with corresponding forms of resistance, for instance, with regard to manifestations of workplace deviance (article 3) and circumvention of corporate language policies (article 4). Thirdly, episodic power is sometimes construed as resistance or enabling power-to versus constraining or limiting systemic power-over. Specifically, this refers to the two case studies on organizational learning and change (article 5) and on labor-management conflict in a university setting (article 6). Fourth, the interplay and mutual reinforcement of the different faces of power is addressed in several contributions. Most explicitly and systematically, it is analyzed in the last article with regard to the psychological processes underlying compliance and (lack of) resistance by academics with the demands of managerialism in the neoliberal university restricting their professional autonomy (article 7). Overall, the reviewed contributions underscore the usefulness of the ‘four faces of power’ as an analytical framework for a broad range of organizational issues, such as contradictory demands and work stress, adoption of or resistance to specific workplace practices, organizational learning and change, and workplace conflict. However, although empirical material was used for illustration purposes, only one study (article 6) used an elaborated and systematic case study approach, including interviews and document analyses. Further well-designed qualitative interview studies seem called for to investigate employee perspectives on the use of different modes of power in organizations. The conceptual analyses presented here provide a solid basis for such outstanding empirical undertakings. Further, although the operationalization of the ‘four faces of power’ with survey measures seems inherently challenging, this should not discourage attempts for conducting quantitative research on power in organizations based on this model. Applied quantitative field research (as opposed to experimental designs) on power in organizations seems especially underdeveloped and, for example, could take the form of comparative analyses of specific configurations of modes of power in different organizations and workforce segments. Issues of particular interest for future research are the interplay of different forms of (direct and indirect, episodic and systemic) power and corresponding (individual and collective, hidden and open) employee resistance.

Limitations

Any review of theories and manifestations of power in organizations remains necessarily limited due to the breadth and depth of the literature. This limitation applies to both the review of theories and taxonomies of power as well as the presented review of applications of the ‘four faces of power’ taxonomy, which should be regarded as preliminary and in need of further refinement. Although a careful screening of the literature suggests that the identified seven articles comprise the full body of currently available conceptual and empirical applications of the four faces of power in organizations, more elaborated search strategies in different scientific databases and with more comprehensive and varied search terms should be used to identify (or rule our) potential additional articles, for instance, not published in English-language journals. Another worthwhile approach would be to broaden the inclusion criteria. For example, one interesting application of the four faces of power to platform ecosystems in the gig economy (Hurni et al., 2022) was excluded, as it did not refer to the site of power within organizations. However, as the boundaries of many organizations dissolve, this criterion might become debatable. A further extension of this research would be to include articles that do not explicitly draw on the taxonomy of the four faces, but analyze forms of power along similar lines. More broadly, the study of power could be more thoroughly integrated with the extensive research on management control systems – two closely related yet largely distinct literatures (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2004). Relevant in this respect are, for instance, the recent critical case study on ‘despotic totalism’ at the fraudulent health technology company Theranos (Tourish & Willmott, 2023), and the analysis of ‘technoeconomic despotism’ and hegemonial labor control practices at Amazon’s warehouses (Vallas et al., 2022). These studies further underscore the importance and actuality of analyzing power in organizations and also suggest a possible conceptual differentiation of the four faces of power, which is outlined below.

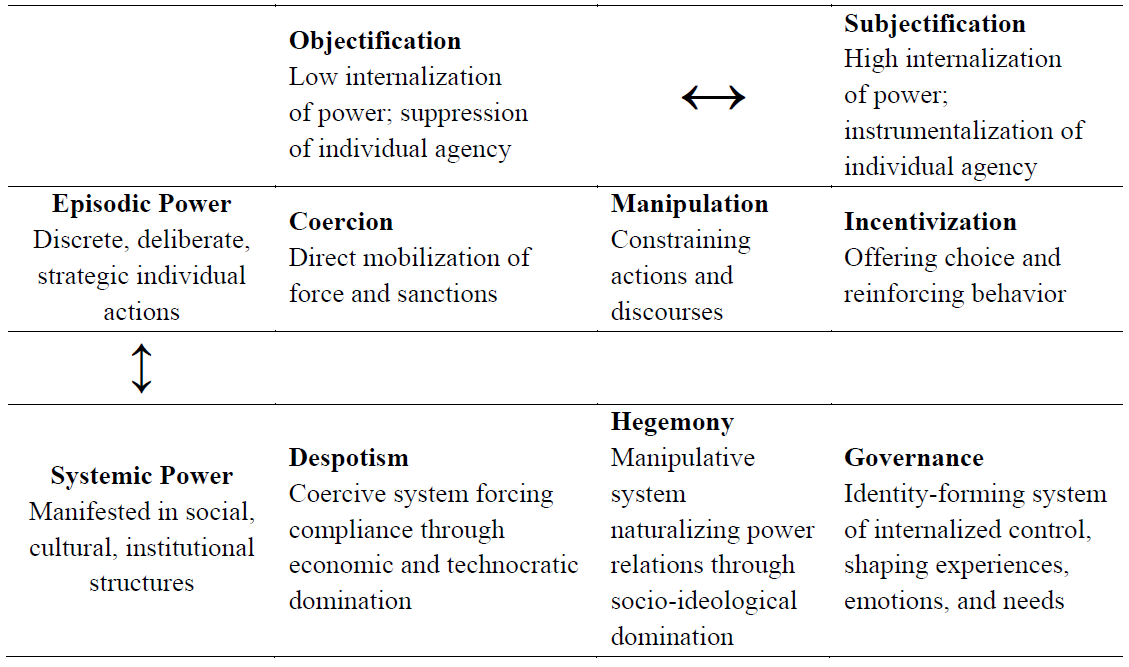

Conceptual extension: From four to six faces of power

Reviewing the broader literature suggests a possible conceptual extension of the four faces of power. Specifically, a further differentiation of the forms of power and their arrangement along two intersecting dimensions could increase the theoretical consistency of the taxonomy. Drawing on the work of labor process theorist Michael Burawoy (1982), studies on organizational control frequently distinguish two forms of systemic domination: Workplace regimes built around coercive controls are termed ‘despotic’, whereas those capitalizing on ideological control by engineering employee consent and commitment, are referred to as ‘hegemonic’ – with hybrid forms analyzed as ‘hegemonic despotism’ (Purcell & Brook, 2022; Tourish & Willmott, 2023). Matching episodic and systemic forms of power, it can be argued that the aggregate of institutionalized episodic power acts of coercion and manipulation correspond with systemic manifestations of despotism and hegemony, respectively. These two forms of systemic power also correspond to workplace regimes of technocratic versus socio-ideological management control (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2004). Systemic power through subjectification, in turn, is based on regimes that episodically offer and incentivize certain choices, providing justifications or patterns of meanings for the elicited responses (Alvesson & Willmott, 2002). However, as subjectification describes more of a process dimension (Hornung et al., 2022), here the often synonymously used term ‘governance’ is suggested to describe systems that shape the sense of self by influencing processes of identity construction, including experiences, emotions, preferences, and needs (Vallas et al., 2022). Accordingly, six faces of power can be theoretically distinguished with coercion, manipulation, and incentivization as the episodic ‘building blocks’ of institutionalized systemic despotism, hegemony, and governance. In addition to the episodic–systemic distinction, these six manifestations can be allocated along an objectification–subjectification dimension. The latter refers to increasing psychological internalization of power and instrumentalization of individual agency in the process of social influence, as suggested in the model by Lawrence and Robinson (2007). The suggested sexpartite taxonomy is illustrated in Figure 1. This revised taxonomy has several advantages as it fully acknowledges the distinction between objectifying despotic and hegemonic systems of domination as well as the growing scientific body of work on advanced forms of subjectivized control through governmentality and biopower. Arranging the resulting six ideal-typical forms along two intersecting continuous dimensions also illustrates that forms of power are a matter of degree and can be described by the extent that their manifestations are a) more episodic versus more systemic in nature and b) based on the extent of objectification versus subjectification of targets, suppressing or instrumentalizing their individual agency within the exercise of power. Systematically thinking about modes or ‘faces’ of power in these categories can advance both theorizing and empirical research.

Suggested conceptual extension from four to six faces of power

Conclusion

The focus on power and control offers a comprehensive paradigm for understanding work organizations. The present review attempts to integrate theories and taxonomies that are rather fragmented and dispersed across the interdisciplinary literature. Especially those subfields of mainstream organizational research that typically neglect or downplay issues of power, such as leadership and careers, employee attitudes, commitment and performance, and occupational health and well-being, would benefit from adopting a power perspective to make sense of their results in a different light. This article provides a number of starting points regarding theoretical foundations, taxonomies, and applications of the multiple manifestations of power in organizational contexts. As power is pervasive in organizations, and as ideology is meaning in the service of power, seeking to construct meaning in this domain without close attention to issues of power risks falling short of a social science of management and organizations, instead proliferating pseudo-scientific managerial ideologies of organizations and organizing.

References

Abizadeh, A. (2023). The grammar of social power: power-to, power-with, power-despite and power-over. Political Studies, 71(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321721996941

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2004). Interfaces of control. Technocratic and socio-ideological control in a global management consultancy firm. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(3-4), 423-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00034-5

Alvesson, M., & Spicer, A. (2016). (Un) Conditional surrender? Why do professionals willingly comply with managerialism. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(1), 29-45. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2015-0221

Alvesson, M., & Szkudlarek, B. (2021). Honorable surrender: on the erosion of resistance in a university setting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(4), 407-420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492620939189

Alvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (2002). Identity regulation as organizational control: producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies, 39(5), 619-644. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305

Augoustinos, M. (1999). Ideology, false consciousness and psychology. Theory & Psychology, 9(3), 295-312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354399093002

Azim, A. N., & Boseman, F. G. (1975). An empirical assessment of Etzioni's topology of power and involvement within a university setting. Academy of Management Journal, 18(4), 680-689. https://doi.org/10.5465/255371\

Bal, P. M., & Dóci, E. (2018). Neoliberal ideology in work and organizational psychology. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(5), 536-548. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1449108

Barley, S. R., & Kunda, G. (1992). Design and devotion: surges of rational and normative ideologies of control in managerial discourse. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(3), 363-399. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/2393449

Berti, M., & Simpson, A. V. (2021). The dark side of organizational paradoxes: the dynamics of disempowerment. Academy of Management Review, 46(2), 252-274. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0208

Braverman, H. (1974). Labor and monopoly capital: the degradation of work in the twentieth century. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press. https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-026-03-1974-07_1

Burawoy, M. (1982). Manufacturing consent: changes in the labor process under monopoly capitalism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Carlsen, A., Clegg, S. R., Pitsis, T. S., & Mortensen, T. F. (2020). From ideas of power to the powering of ideas in organizations: reflections from Follett and Foucault. European Management Journal, 38(6), 829-835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.03.006

Carson, P. P., Carson, K. D., & Roe, C. W. (1993). Social power bases: a meta‐analytic examination of interrelationships and outcomes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(14), 1150-1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01026.x

Clegg, S. (2009). Foundations of organization power. Journal of Power, 2(1), 35-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17540290902760873

Collien, I. (2021). Concepts of power in boundary spanning research: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(4), 443-465. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12251

Collinson, D. (2020). ‘Only connect!’: exploring the critical dialectical turn in leadership studies. Organization Theory, 1(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787720913878

Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2(3), 201-215. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303

Digeser, P. (1992). The fourth face of power. The Journal of Politics, 54(4), 977-1007. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i337410

Dirik, D., & Eryılmaz, İ. (2018). Leader power bases and organizational outcomes. Journal of East European Management Studies, 23(4), 532-558. http://dx.doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2018-4-532

Dodge, C. (2016). Compliance theory of organizations. In A. Farazmand (ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3000-1

Elias, S. (2008). Fifty years of influence in the workplace: the evolution of the French and Raven power taxonomy. Journal of Management History, 14(3), 267-283. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511340810880634

Etzioni, A. (1975). A comparative analysis of complex organizations: on power, involvement, and their correlates (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Fleming, P. (2014). When ‘life itself’ goes to work: reviewing shifts in organizational life through the lens of biopower. Human Relations, 67(7), 875-901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726713508142

Fleming, P. (2022). How biopower puts freedom to work: conceptualizing ‘pivoting mechanisms’ in the neoliberal university. Human Relations, 75(10), 1986-2007. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267221079578

Fleming, P., & Spicer, A. (2014). Power in management and organization science. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 237-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.875671

Foldy, E. G., & Ospina, S. M. (2023). ‘Contestation, negotiation, and resolution’: the relationship between power and collective leadership. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(3), 546-563. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12319

Foster, R. (2017). Social character: Erich Fromm and the ideological glue of neoliberalism. Critical Horizons, 18(1), 1-18. http://doi.org/10.1080/14409917.2017.1275166

Foulk, T. A., Chighizola, N., & Chen, G. (2020). Power corrupts (or does it?): an examination of the boundary conditions of the antisocial effects of experienced power. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(4), e12524. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12524

Glaser, J., Hornung, S., & Höge, T. (2019). Organizational tensions, paradoxes, and contradictory demands in flexible work systems. Journal Psychologie des Alltagshandelns / Psychology of Everyday Activity, 12(2), 21-32.

Greer, L. L., Van Bunderen, L., & Yu, S. (2017). The dysfunctions of power in teams: a review and emergent conflict perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior, 37(6), 103-124. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.005

Haugaard, M. (2022). Foucault and power: a critique and retheorization. Critical Review, 34(3-4), 341-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2022.2133803

Hargrave, T. J., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2017). Integrating dialectical and paradox perspectives on managing contradictions in organizations. Organization Studies, 38(3-4), 319-339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640843

Hekkala, R., Stein, M. K., & Sarker, S. (2022). Power and conflict in inter‐organisational information systems development. Information Systems Journal, 32(2), 440-468. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12335

Heller, S., Ullrich, J., & Mast, M. S. (2023). Power at work: linking objective power to psychological power. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 53(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12922

Hornung, S. (2010). Alienation matters: validity and utility of Etzioni's theory of commitment in explaining prosocial organizational behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 38(8), 1081-1095. http://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.8.1081

Hornung, S., & Höge, T. (2021). Analysing power and control in work organizations: assimilating a critical socio-psychodynamic perspective. Business & Management Studies: An International Journal, 9(1), 355-371. http://doi.org/10.15295/bmij.v9i1.1754

Hornung, S., & Höge, T. (2024). Analyzing current debates in management and organization studies: a meta-theoretical review and dialectic interpretation. Scientia Moralitas – International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 9(2), 1-32. Retrieved from https://www.scientiamoralitas.com/index.php/sm/article/view/260

Hornung, S., Weigl, M., Lampert, B., Seubert, C., Höge, T., & Herbig, B. (2022). Societal transitions of work and health from the perspective of subjectification – critical synthesis of selected studies from applied psychology. Journal Psychologie des Alltagshandelns / Psychology of Everyday Activity, 15(1), 5-24.

Hurni, T., Huber, T. L., & Dibbern, J. (2022). Power dynamics in software platform ecosystems. Information Systems Journal, 32(2), 310-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12356

Ivanova, M., & von Scheve, C. (2020). Power through empowerment? The managerial discourse on employee empowerment. Organization, 27(6), 777-796. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419855709

Jost, J. T. (1995). Negative illusions: conceptual clarification and psychological evidence concerning false consciousness. Political Psychology, 16(2), 397-424. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791837

Klikauer, T. (2019). A preliminary theory of managerialism as an ideology. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 49(4), 421-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12220

Knights, D., & Willmott, H. (1985). Power and identity in theory and practice. The Sociological Review, 33(1), 22-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1985.tb00786.x

Langer, S. (2023). The relation of standards and power in management and organization research: core notions and alternative avenues. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(4), 647-665. http://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12325

Lawrence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2007). Ain't misbehavin: workplace deviance as organizational resistance. Journal of Management, 33(3), 378-394. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300816

Lawrence, T. B., Malhotra, N., & Morris, T. (2012). Episodic and systemic power in the transformation of professional service firms. Journal of Management Studies, 49(1), 102-143. http://doi.org/j.1467-6486.2011.01031.x

Lémonie, Y., Grosstephan, V., & Tomás, J. L. (2021). From a sociological given context to changing practice: transforming problematic power relations in educational organizations to overcome social inequalities. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 608502. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608502

Liao, E. Y., Wang, A. Y., & Zhang, C. Q. (2021). Who influences employees’ dark side: a multi-foci meta-analysis of counterproductive workplace behaviors. Organizational Psychology Review, 11(2), 97-143. http://doi.org/10.1177/2041386620962554

Lilja, M., & Vinthagen, S. (2014). Sovereign power, disciplinary power and biopower: resisting what power with what resistance? Journal of Political Power, 7(1), 107-126. http://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2014.889403

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: a radical view (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2065624

Lukes, S. (2022). Bringing power back in. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22(1), 130-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X211055659

McKinlay, A., Carter, C., & Pezet, E. (2012). Governmentality, power and organization. Management & Organizational History, 7(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744935911429414

Moisander, J., Groß, C., & Eräranta, K. (2018). Mechanisms of biopower and neoliberal governmentality in precarious work: mobilizing the dependent self-employed as independent business owners. Human Relations, 71(3), 375-398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717718918

Mumby, D. K. (2015). Organizing power. Review of Communication, 15(1), 19-38. http://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2015.1015245

Munro, I. (2012). The management of circulations: biopolitical variations after Foucault. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(3), 345-362. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00320.x

Murt, M. F. (2020). A concept analysis of power. Nursing Forum, 55(4), 737-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12491

Ocasio, W., Pozner, J. E., & Milner, D. (2020). Varieties of political capital and power in organizations: a review and integrative framework. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 303-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0062

Omidi, A., Dal Zotto, C., & Gandini, A. (2023). Labor process theory and critical HRM: a systematic review and agenda for future research. European Management Journal, 41(6), 899-913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.05.003

Pansardi, P., & Bindi, M. (2021). The new concepts of power? Power-over, power-to and power-with. Journal of Political Power, 14(1), 51-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2021.1877001

Penley, L. E., & Gould, S. (1988). Etzioni's model of organizational involvement: a perspective for understanding commitment to organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 43-59. https:///doi.org/10.1002/job.4030090105

Peiró, J. M., & Meliá, J. L. (2003). Formal and informal interpersonal power in organisations: testing a bifactorial model of power in role‐sets. Applied Psychology, 52(1), 14-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00121

Purcell, C., & Brook, P. (2022). At least I’m my own boss! Explaining consent, coercion and resistance in platform work. Work, Employment and Society, 36(3), 391-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020952661

Raven, B. H. (2008). The bases of power and the power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 8(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2008.00159.x

Reed, M. I. (2012). Masters of the universe: power and elites in organization studies. Organization Studies, 33(2), 203-221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611430590

Schilbach, M., Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2020). Why employee psychopathy leads to counterproductive workplace behaviours: an analysis of the underlying mechanisms. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(5), 693-706. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1739650

Schildt, H., Mantere, S., & Cornelissen, J. (2020). Power in sensemaking processes. Organization Studies, 41(2), 241-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619847718

Schirmer, F., & Geithner, S. (2018). Power relations in organizational change: an activity-theoretic perspective. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 14(1), 9-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-11-2016-0074

Seeck, H., Sturdy, A., Boncori, A. L., & Fougère, M. (2020). Ideology in management studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22(1), 53-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12215

Shatil, S. (2020). Managerialism–a social order on the rise. Critical sociology, 46(7-8), 1189-1206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520911703

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Sturm, R. E., & Antonakis, J. (2015). Interpersonal power: a review, critique, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41(1), 136-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314555769

Tost, L. P. (2015). When, why, and how do powerholders “feel the power”? Examining the links between structural and psychological power and reviving the connection between power and responsibility. Research in organizational behavior, 35(4), 29-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2015.10.004

Tost, L. P., & Johnson, H. H. (2019). The prosocial side of power: how structural power over subordinates can promote social responsibility. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 152, 25-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.04.004

Tourish, D., & Willmott, H. (2023). Despotic leadership and ideological manipulation at Theranos: towards a theory of hegemonic totalism in the workplace. Organization Studies, 44(11), 1801-1824. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406231171801

van Baarle, S., Bobelyn, A. S., Dolmans, S. A., & Romme, A. G. L. (2024). Power as an enabling force: an integrative review. Human Relations, 77(2) 143-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267221128561

Vaara, E., & Whittle, A. (2022). Common sense, new sense or non‐sense? A critical discursive perspective on power in collective sensemaking. Journal of Management Studies, 59(3), 755-781. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12783

Vallas, S. P., Johnston, H., & Mommadova, Y. (2022). Prime suspect: mechanisms of labor control at amazon's warehouses. Work and Occupations, 49(4), 421-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07308884221106922

Weiskopf, R., & Loacker, B. (2006). “A snake's coils are even more intricate than a mole's burrow”: individualization and subjectification in post-disciplinary regimes of work. Management Revue, 17(4), 395-419. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/78939

Wilmot, N. V. (2017). Language and the faces of power: a theoretical approach. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 17(1), 85-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817694915

Winkler-Titus, N. V., & Crafford, A. (2022). Resistance: faces of power and how identity is reflected. South African Journal of Business Management, 53(1), a3089. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v53i1.3089

Download Count : 94

Visit Count : 318

Keywords

Power in Organizations; Four Faces of Power; Coercion; Manipulation; Domination; Subjectification; Literature Review

How to cite this article:

Hornung, S. (2024). Faces of Power in Organizations: Foundations, Applications, and Extension. International Journal of Behavior Studies in Organizations, 12, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32038/jbso.2024.12.01

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented at the 11th International Conference on Management Studies and Social Sciences (ICMS & ICSS 2024), convened on August 10, 2024, in Istanbul, Turkey.

Funding

No funding was received from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest pertaining to this research.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/