Original Research

First Steps towards Ecosystemic Governance for Health and Recreational Tourism Destinations

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

The concept of the business ecosystem emerged at the turn of the century, drawing inspiration from biology to describe the economic community. Since its inception, this concept has found applications across various domains, including technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship, where it significantly contributes to strategic management. However, within the realm of tourism, there remains a notable dearth of literature on this subject. While it is acknowledged that tourism destinations embody many characteristics of a business ecosystem, concrete tools for adopting an ecosystemic approach in tourism management, particularly across different tourism types, are lacking. The current study seeks to address this gap by undertaking a theoretical exploration of health and recreational tourism. It aims to identify socio-economic aspects that could facilitate the adoption of an ecosystemic approach in the governance of tourism destinations, with a specific focus on these types of tourism. As a result of this endeavor, an initial model delineating the ecosystem of a health and recreational tourism destination is proposed. This model lays the groundwork for empirical validation and further refinement through subsequent studies.

First Steps towards Ecosystemic Governance for Health and Recreational Tourism Destinations

Rositsa Röntynen

Varna Free University “Chernorizets Hrabar”, Varna, Bulgaria

Abstract:

The concept of the business ecosystem emerged at the turn of the century, drawing inspiration from biology to describe the economic community. Since its inception, this concept has found applications across various domains, including technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship, where it significantly contributes to strategic management. However, within the realm of tourism, there remains a notable dearth of literature on this subject. While it is acknowledged that tourism destinations embody many characteristics of a business ecosystem, concrete tools for adopting an ecosystemic approach in tourism management, particularly across different tourism types, are lacking. The current study seeks to address this gap by undertaking a theoretical exploration of health and recreational tourism. It aims to identify socio-economic aspects that could facilitate the adoption of an ecosystemic approach in the governance of tourism destinations, with a specific focus on these types of tourism. As a result of this endeavor, an initial model delineating the ecosystem of a health and recreational tourism destination is proposed. This model lays the groundwork for empirical validation and further refinement through subsequent studies

Keywords: Tourism Destination Governance, Business Ecosystem, Health Tourism, Recreational Tourism

The concept of the business ecosystem emerged at the turn of the century, drawing inspiration from biology to describe the economic community. Since its inception, this concept has found applications across various domains, including information technology (e.g., Basole, 2009; De Tommassi et al., 2005; Iyer et al., 2006), innovation (e.g., den Hartigh & van Asseldonk, 2004; Thomas & Autio, 2012), and entrepreneurship (e.g., Spigel, 2015), where it significantly contributes to strategic management. However, within the realm of tourism, there remains a notable dearth of literature on this subject. While it is acknowledged that tourism destinations embody many characteristics of a business ecosystem (e.g., Henche et al., 2020; Kylänen & Rusko, 2011; Milwood & Crick, 2021; Selen & Ogulin, 2015), concrete tools for adopting an ecosystemic approach in tourism management, particularly across different tourism types, are lacking.

The current study seeks to address this gap by undertaking a theoretical exploration of health and recreational tourism. These particular types of tourism are a contemporary matter of interest because of trends like the increased interest in personal health (Hjalager et al., 2011; Lindell et al., 2019; Varga & Csákvári, 2019), the aging global population (Csrimaz & Pető, 2015; Georgiev & Vasileva, 2009; Hojcska, 2023; Ullah et al., 2021) the tourism expansion into the realm of recreation, and the increased consumer interest in nature-based tourism (Hall & Page, 2006; Kostova, 2014; Lück & Aquino, 2021). While health and recreational tourism represent a categorization according to the main motive for the tourism visits, they include various types of tourism according to the locations and practiced activities, covering a large extent of leisure tourism. For this reason, their exploration provides value for many other types of tourism.

The research question of the study is: Which socio-economic aspects could facilitate the adoption of an ecosystemic approach in the governance of health and recreational tourism destinations? To answer this, a literature review chapter first goes through the relevant concepts related to business ecosystems, health, and recreational tourism. Further, the methodology of the study is presented. The exploration leads to an initial model delineating the ecosystem of a health and recreational tourism destination. Finally, the results of the study and their implications are discussed to advise future research.

Literature Review

Ecosystemic Approach to Tourism Management

By definition, a business ecosystem is a “growth oriented synergistic” economic community of “mutually supportive” agents from both the production and consumption side (Moore, 1998, p. 168), going beyond the boundaries of a conventional network. They come together “in a partially intentional, highly self-organizing, and even somewhat accidental manner” (Moore, 1998, p. 169) to achieve a common goal, e.g., the satisfaction of a customer’s need (Moore, 1993). Business science adopted the biological ecosystem model to analyze relationships and strategic decision-making amidst significant changes in the competitive environment due to rapid technological advances, the information age, and globalization (Iansiti & Levien, 2004a, 2004b; Peltoniemi & Vuori, 2005). Tourism is a prime example of a business ecosystem due to its multilateral, fragmented, and complex character, as well as its various connections to other sectors (Baggio, 2008; Scott, Baggio et al., 2009). Tourism functions as an experience economy, where delivering successful experiences is vital for organizations facing industry changes such as new destinations, strong competition, and new technologies (Buonincontri et al., 2017). Tourist service providers, including tour operators, hotels, cruise lines, activity providers, and destination management organizations (DMOs), must collaborate within a network of agents such as customers, authorities, special interest groups, local communities, and co-suppliers (Hillebrand, 2022). Interconnectedness and cooperation are essential for the tourism product (Björk & Virtanen, 2005), which also corresponds to Moore’s (1996) total experience including complementary offers. The ecosystem approach is particularly relevant in complex situations like radical innovations or sustainable tourism development (Hillebrand, 2022), as the industry consists of many small actors who cannot achieve common goals alone (Halme, 2001).

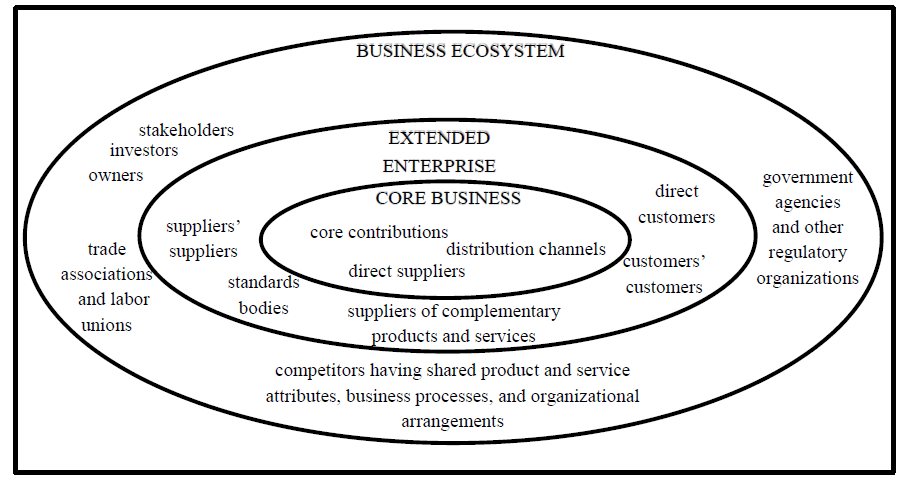

The business ecosystem described by Moore (1996) comprises of three layers: core business, extended enterprise, and business ecosystem (Figure 1). It accounts for the different participating agents from the perspective of the individual business but does not indicate their role within the ecosystem context. Other authors (Hillebrand, 2022; Iansiti & Levien, 2004b) define the ecosystem agents by their function, i.e., keystone, niche player, dominator, hub landlord, shaper, follower, adapter, reserving the right to play, and broker. However, it is not clear how these roles can be incorporated into the level structure of the ecosystem described by Moore.

Structure of the Business Ecosystem According to Moore (1996)

Important information about situating the ecosystem agents could be found in another research. According to Thomas and Autio (2012), a locus of coordination (LoC) is essential for the institutional stability of the business ecosystem. This central agent unites all participants and provides tools for generating and distributing value through governance mechanisms, such as shared values, norms, rules, and agreements, which create a framework for value co-creation and symbiosis, thereby reducing the ecosystem's complexity. Hillebrand (2022) distinguishes between influencers and the influenced. Agents that neither affect nor are affected by value are irrelevant and exit the ecosystem. Agents that affect value but are not affected by it are necessary, providing essential resources for the ecosystem's success. Agents that both influence and are influenced by value are interdependent. Finally, agents that are influenced by value but lack resources to influence it are considered remote agents.

The tourism destination is more than a geographic location. It comprises attractions, facilities, and services, economic, social, and environmental factors, core competencies, leadership, knowledge flow, and entrepreneurship (Baggio, 2008; Brawn, 2005). Moreover, it is defined by the tourist’s choice to visit (Selen & Ogulin, 2015). To keep all these features of the destination together, tourism relies on two important specific agents, namely the visitors and the locals. Locals are tourism-specific stakeholders (March & Wilkinson, 2009) who serve as both a resource for tourism and a driving force behind tourism development in a location (Richards & Hall, 2002). However, in many instances, they have limited resources to influence value and are often overlooked as remote agents (Hillebrand, 2022). Customers are agents of the business ecosystem and, in the tourism context, are the tourists or visitors. They cooperate with economic agents to co-create tourism products. Tourists influence their experiences and other tourists by interacting with destination service providers in person and through technology (Buonincontri et al., 2017; Milwood & Crick, 2021). Technology significantly enhances this co-creation by offering more information, transparency, dynamics, and user orientation (Buonincontri et al., 2017). If visitors as customers decide to leave the ecosystem, this could potentially destroy its value for the rest of the participating agents (den Hartigh & van Asseldonk, 2004). The role of the visitors is also discussed in relation to destinations in protected areas (Taff et al., 2019), where the environmental impacts are preferably minimized by indirect governance, including education and communication, which corresponds to the ecosystem’s soft-power governance, to preserve visitor choices, optimizing recreational benefits, and fostering responsible behavior.

Socio-economic Particulars of Health and Recreational Tourism

Health and recreational tourism are rapidly growing (Albuquerque et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2021) contemporary alternative tourism types (Hristov, 2011; Lück & Aquino, 2021; Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020), driven by powerful trends, such as the aging population (Csrimaz & Pető, 2015; Georgiev & Vasileva, 2009; Hojcska, 2023; Ullah et al., 2021), the growing interest in and self-responsibility for personal health (Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Hjalager, 2011; Lindell et al., 2019; Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020; Quintela et al., 2016; Varga & Csákvári, 2019), the stress related to modern lifestyle (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Cherian & Benfield, 2018; Cracknell et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2023; Lindell et al., 2019; Lück & Aquino, 2021), and the boom of nature-based tourism (Hall & Page, 2006; Kostova, 2014; Lück & Aquino, 2021), and facilitated by others, like the improved international transportation, the expansion of communication networks, and the seamless transfer of technological innovations between countries (Toksöz, 2021).

Health tourism is used as an umbrella term for a variety of health-enhancing travel activities (Albuquerque et al., 2018; Quintela et al., 2016). They are ranging from invasive (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Langvinienė, 2014; Quintela et al., 2016), curative (Georgiev & Vasileva, 2009; Hojcska, 2023; Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020; Mihaylov, 2012) and rehabilitative (Langvinienė, 2014; Liao et al., 2023; Mihaylov, 2012; Wagenaar & Vaandrager, 2018), usually related to medical tourism (e.g., Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Hojcska, 2023; Horváth, 2023; Lindell et al., 2019; Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020; Palancsa, 2023; Palkovics & Varga, 2023; Toksöz, 2021; Voigt et al., 2011), to preventive (Chen et al., 2008; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Quintela et al., 2016; Varga et al., 2018), rejuvenating, relaxing (Albuquerque et al., 2018; Csrimaz & Pető, 2015; Georgiev & Vasileva, 2009; Liao et al., 2023; Quintela et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023; Yanakieva & Karadzhova, 2020) and even pampering (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Albuquerque et al., 2018; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Langvinienė, 2014), often regarded as wellness or well-being tourism (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 2018; Cavicchi et al., 2018; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Davchev, 2014; Konu et al., 2011; Lindell et al., 2019; Smith & Puczkó, 2014; Szymańska, 2015).

Health tourism relies to a large extent on professional, qualified healthcare staff, in addition to the tourism personnel (Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Mihaylov, 2012; Toksöz, 2021), and on specialized facilities and infrastructure, such as health centers and hospitals, rehabilitation centers, health resorts, sports facilities, spa centers, and sanatoria (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Bogomolova & Dovlatova, 2019; Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Langvinienė, 2014; Liao et al., 2023; Mihaylov, 2012; Lindell et al., 2019; Ullah et al., 2021), as well as on innovative technological solutions (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Palancsa, 2023). These features constitute, on the one hand, the participation of agents external to the tourism industry in the service supply (e.g., Cracknell et al., 2018; Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Ullah et al., 2021; Steckenbauer et al., 2018; Palancsa, 2023; Zhong et al., 2021), and on the other hand, the non-seasonal character of the health tourism activity (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Albuquerque et al., 2018; Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020; Scott, de Freitas et al., 2009; Yanakieva & Karadzhova, 2020). Furthermore, the literature presents higher education institutions as co-creators of wellbeing services (Cavicchi et al., 2018).

Despite the non-seasonality and the strong presence of built indoor facilities, health tourism relies strongly on natural resources as well (e.g., Zhong et al., 2021). Natural resources can serve as a foundation for developing unique, geographically specific products, aiming to establish a distinctive market position and appeal of the destination and providing a competitive advantage by offering experiences that cannot be replicated elsewhere (Smith & Puczkó, 2008). Many of nature’s characteristics, such as landscape, climate, and water, have medically proven effects on human health and well-being (Smith & Diekmann, 2017). Tourism centers and sanatoria are built in Bulgaria based on mineral springs and mud therapy (Mihaylov, 2012; Yanakieva & Karadzhova, 2020). In Poland, some wellness tourism products are based on the positive influence of maritime climate incorporated in various therapies (Lindell et al., 2019). In Hungary, health tourism is typically based on natural healing factors like healing water, healing mud, healing climate, or healing cave (Palkovics & Varga, 2023). Merdivenci and Karakaş (2020) go even further and, in the context of Turkish health tourism, stating that countries with attractive destination features, such as cultural and historical sites, beaches, political and economic stability, hospitality, and high service quality, are more likely to excel in the competitive tourism market. According to Liao et al. (2023), most wellness tourists prefer destinations with a more favorable climate and a more appealing natural environment, such as forests, parks, water bodies, and coastal areas, than their usual residence place. South Africa’s medical tourism is marketed as “surgery and safari” and “sea, sun, and surgery” (Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024, 436). Health tourism impacts the environment not only when it is implemented directly in nature, but the available management tools, such as land use zoning, carrying capacity analysis, and limits of acceptable change assessments, only cover the effects of outdoor recreation (Ullah et al., 2021). The presence of appropriate and sufficient infrastructure supports health tourism by decreasing operational costs and widening the market opportunities (Ullah et al., 2021).

For quality assurance and safety, health tourism products and services should be evidence-based, and institutions should be accredited or certified, which is not always the case (Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Horváth, 2023; Steckenbauer et al., 2018). Health tourism is closely linked to legislation and regulations (Georgiev & Vasileva, 2009; Hojcska, 2023), which emphasizes the influence of governmental authorities on its activity. This is especially valid for medical tourism, whose demand and supply depend on the regulations and availability of medical services not only in the destination but also in the home country of the visitor (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 2018; Deonarain & Rampersad, 2024; Palancsa, 2023). Health tourism services could be available through private (self-financed) or public funding (government subsidies) depending on the legislation (Davchev, 2014; Lindell et al., 2019; Mihaylov, 2012; Palkovics & Varga, 2023; Hojcska, 2023; Tribe, 2004).

The customers of health tourism do not represent a homogeneous group, which should be considered in the management of the destination. A major difference that needs to be considered is that the customers of medical procedures incorporated in medical tourism usually act out of necessity, while the customers of disease-preventive and health-enhancing treatments participate in these activities voluntarily (Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015). Ullah et al. (2021) suggest three separate segments: the youth sports tourism market, the middle-aged health care tourism market, and the elderly pension tourism market, all of which suggest the cooperation of the tourism industry with different organizations to acquire these potential customers. Those temporarily or permanently disabled are also customers of health tourism and need accessible options (Merdivenci & Karakaş, 2020; Toksöz, 2021; Wagenaar & Vaandrager, 2018).

Recreational tourism is not unambiguously defined. Firstly, in the literature, albeit conditional and based on perceptions (McKercher, 1996), there is a division of leisure time into recreation and tourism, which to some extent opposes these two concepts, although there is overlap between them (Hall & Page, 2006; Tribe, 2004). In this sense, recreation considers rather local behavior, often related to outdoor activity, rather in a non-commercial dimension (Hall & Page, 2006). On the other hand, tourism is seen through the prism of mobility, usually related to long-distance transfer (within the country or abroad), and usually includes overnight stays and economic consumption (Hall & Page, 2006; McKercher, 1996). However, this division is increasingly contradicted by new trends in tourism. In recent times and especially after the COVID pandemic, local (short-distance) tourism is gaining popularity (Nokkala, 2023), and with the growing interest in nature-based tourism (Hall & Page, 2006; Kostova, 2014; Lück & Aquino, 2021), more and more outdoor recreational practices are being incorporated into tourism. Recreation is also recognized as one of the main motivations for travel (Gjorgievski et al., 2013).

Secondly, recreational tourism is not strictly distinguished from health tourism (e.g., Bogomolova & Dovlatova, 2019; Csrimaz & Pető, 2015; Hansen, 2018; Hjalager et al., 2011; Yanakieva & Karadzhova, 2020), but includes some common manifestations organized around prevention and health for the healthy (Mihaylov, 2012). Many of the subtypes, such as SPA tourism, well-being tourism, and wellness tourism, are overlappingly considered recreational and health tourism (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Mihaylov, 2012; Varga & Csákvári, 2019). This is also determined by modern trends related to increased interest and responsibility for personal health (e.g., Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015).

Thirdly, the concept of recreational tourism is preferred on a regional basis, especially in Central and Eastern Europe and in Slavic-speaking countries (e.g., Bogomolova & Dovlatova, 2019; Csrimaz & Pető, 2015; Gjorgievski et al., 2013; Mihaylov, 2012; Varga & Csákvári, 2019), while linguistic and cultural peculiarities in other countries have imposed the concepts of wellness tourism (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2008; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015) and, more recently, wellbeing tourism (Hjalager et al., 2011; Konu et al., 2011; Lindell et al., 2019), which include similar characteristics, but which do not have a direct equivalent in the respective languages, e.g., in Bulgarian. In many languages, for example, in Finnish, there is only one word for well-being, without the possibility of dividing wellness and wellbeing (Konu et al., 2011). In a broader sense, wellness can also be perceived as the absence of illness (Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015) and as the prevention of disease conditions (e.g., Liao et al., 2023). Wagenaar and Vaandrager (2018), however, remind us that there is no strict dichotomy between health and disease, especially in the context of people living with a disability. Wellbeing and wellness tourism, similarly to recreational tourism, are associated with the establishment or re-establishment of the balance between physical, mental, and social strengths (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 2018; Bogomolova & Dovlatova, 2019; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Mihaylov, 2012; Ullah et al., 2021).

Recreational tourism relies largely on nature’s resources. Nature is seen as a major source of experiences and wellbeing (Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015). At the same time, recreational tourism destinations, businesses and products involving immobile capital assets have a small adaptive capacity to climate change, while transportation services, tour operators, and tourists have a greater degree of freedom and thus can react to climate change, e.g., substituting spatial, temporal and activity aspects related to tourism (Scott, de Freitas et al., 2009). Natural recreational resources exist independently of tourism activity and have value in their original form but are used by tourists to satisfy their recreational needs; however, they are complemented by anthropogenic resources, created especially for the purpose of recreation (Gjorgievski et al., 2013; Lee, 2016). Infrastructure is also paramount for recreational tourism. It does not only enable recreational activities but it establishes the accessibility and safety of the destination (Lee, 2016). To serve the locals and the travelers, accommodation, catering, transportation, and information services should be included in the recreational offer (Lee, 2016).

Recreational tourism ranges from adventurous, e.g., diving, climbing, through active, e.g., skiing, snowshoeing, golf, horse riding, trail running, to light, relaxing, and passive, e.g., sensory walks (Ahtiainen et al., 2015; Grénman & Räikkönen, 2015; Hansen, 2018; Quintela et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2021), catering for a variety of customers with different abilities and interests. It is noticed that destinations based on the complexity of resources, offering different activities to different segments in different seasons, have the greatest potential for recreational tourism (Gjorgievski et al., 2013). Another perspective to recreational tourism customers is that recreation is a primer for leisure travelers, while for business travelers, it is a secondary activity (Gjorgievski et al., 2013). Furthermore, Hansen (2018) recognizes not only tourists but also day visitors, secondary homeowners, and permanent residents as recreational groups using the same infrastructure and services. The wide range of stakeholders participating in different recreational activities using the same resources and infrastructure could create conflicts and negative ecological impacts; thus, strong communication and wide stakeholder inclusion in the development and management of nature-based recreational tourism destinations are recommended (Bishop et al., 2022; Derriks, 2018).

Method

The study integrates literature on business ecosystems with health and recreational tourism to create a conceptual model of a health and recreational tourism destination ecosystem. An integrative literature review approach is chosen (Snyder, 2019), enabling the development of new frameworks (Torraco, 2005). The integrative review helps create an initial conceptual model and sets an agenda for further research.

Relevant literature was selected from several scientific databases and complemented by a Google search for grey literature. The keyword “business ecosystem” was used for ecosystem literature, with complete reading to filter sources effectively. The term was distinguished from similar concepts like networks, entrepreneurial, and service ecosystems. Articles that used the term without addressing the concept were excluded. Due to the rarity of tourism-specific business ecosystem sources, overarching reviews were also included.

To synthesize research on health and recreational tourism, articles from the last decade were chosen, considering that recent global developments like financial crises, climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and technological advances have reshaped tourism. The snowball technique helped identify additional relevant sources. Initial keywords were “health tourism” and “recreational tourism,” with further keywords like “wellness tourism”, “wellbeing tourism”, “medical tourism”, and “nature-based tourism” emerging. Regional preferences and term discrepancies were addressed by including some non-English articles, including such in Bulgarian, Hungarian, Russian, Turkish, and Finnish. The review critically synthesized aspects such as definitions, subtypes, stakeholders, value creation, and socio-economic implications.

The conceptual framework development aimed at a common model using inductive thematic analysis, allowing iterative refinement of themes. The integration of concepts creates synergies: health and recreational tourism contextualize the business ecosystem within tourism, while the business ecosystem concept offers new tools for governing health and recreational tourism.

Conceptual Model of the Ecosystem of a Health and Recreational Tourism Destination

In terms of strategic management, health tourism has proven to have a significant role in the growth of destinations (Albuquerque et al., 2018; Steckenbauer et al., 2018). The literature on health and recreational tourism emphasizes the necessity of building a complex tourism product, serving a broad range of customers in different seasons by cooperation and dialogue of all key players internal and external to the tourism industry, in and around the destination, and harmonizing this tourism activity with the sustainable use of natural resources. Moreover, the non-seasonality could potentially improve the socio-cultural and economic conditions of local areas (Albuquerque et al., 2018). Therefore, ecosystemic governance is one way to develop such a complex tourism offer and accomplish the sustainability goals of the health and recreational tourism destination.

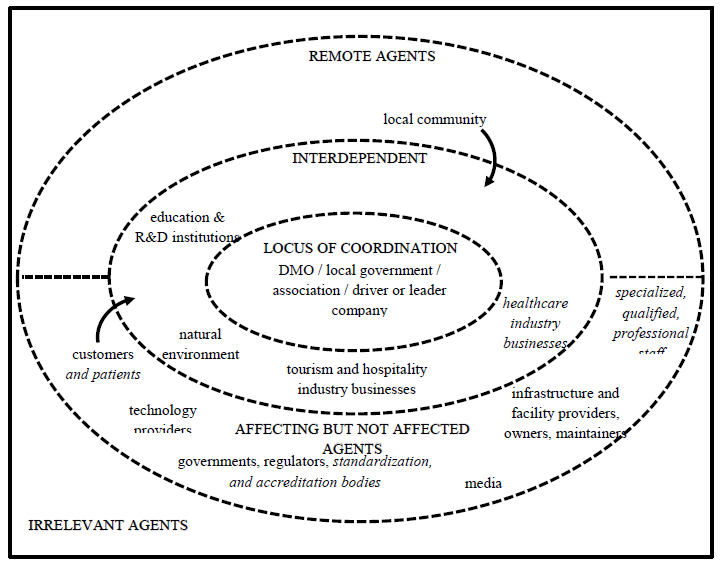

Initial Model of a Health and Recreational Tourism Destination Ecosystem

The first step in the establishment of ecosystemic governance of the health and recreational tourism destination is the recognition of the layers of the destination ecosystem with the agents and the interrelations belonging to each layer. The building of such a model needs to start by flipping Moore’s model of the business ecosystem from enterprise-oriented to destination-centered. Subsequently, the agents of the destination ecosystem are positioned in each of the layers. Finally, an initial model delineating the ecosystem of a health and recreational tourism destination is proposed (Figure 2).

The dashed borders of each ecosystem level symbolize voluntary participation, non-contractual relationships, fluid agent roles, and the possibility of changing positions. Many agents belong to the general tourism ecosystem, while those in italics are specific to health and recreation.

At the center is the locus of coordination, typically a destination management organization, a local government, an association of businesses or a larger, significant driver or leader company influential to the destination, which possesses the sufficient resources, capacities, and competencies to motivate, incentivize, and thus coordinate the participants in the destination ecosystem. The LoC should be aware of its position and govern the destination with soft power instead of dominance, taking care of communication efficiency between agents and distributing information for knowledge-based decision-making across the destination.

The middle layer consists of interdependent agents. This is where competition, the interplay of cooperation and competition of agents, is observed. Most of the tourism and hospitality businesses would typically be positioned here, but also the healthcare providers, in order for the destination to provide health and recreational services. As both health and recreation activities in tourism are closely related to nature, which is their stage, main resource, and competitive advantage of the specific destination, the natural environment itself is an important agent in this layer of the destination. However, nature is not only affecting the product but is also being affected by tourism activity, which calls for responsibility measures and regulations to ensure the environmentally sustainable conduct of tourism. In this layer, significant agents are also research and development, as well as education institutions, which contribute to the health of the ecosystem by driving innovation forward and facilitating the networking of actors cross-disciplinarily.

In the outer layer of the ecosystem, agents are situated, who are affecting value but do not get affected by it. They have significant resources to enable, facilitate, or hinder and even destroy the destination ecosystem and its health and recreation value, for example, by regulation, legislation, standardization, accreditation of the processes, products, and services; by the presence or absence of technological solutions to facilitate the interaction between agents or with the customers, to implement health-related treatments; by coverage and representation of the destination in the conventional or social media; by creating, providing, maintaining the infrastructure and facilities used in but not always existing barely for tourism and its health and recreational occurrences. These agents should constantly be made aware and reminded of their influence on the destination by good communication, and the not so obvious benefit from their participation should be brought to the surface. In this layer, the present or absent specialized staff, not only of tourism but especially of healthcare, also affects the value created by the destination.

Customers also affect value – by their choice to visit the destination by interacting with service providers and other customers. The customers might also be patients in the context of health-restoring visits and treatments. There should be an attempt to include customers in the middle layer of the ecosystem – not only would this be in accordance with the contemporary perception of the customer as a co-creator, but it would also suggest that customers actually receive the transformational benefits of health and recreational tourism. It is important to remember the heterogeneous character of the health and recreational tourism customer. The common traits of the visitors are that they belong to the aging society, are health-aware, usually urbanized and stressed from their daily life, fluent in communication and technology use, and are highly mobile and globalized. Simultaneously, however, they are divergent according to their domestic-international character, their voluntary-involuntary participation, the intent for invasive or non-invasive treatments, the nature, facility, or holistic orientation, the motivation for illness curation or wellness enhancement, the sport and adventure or relaxation and slow-down drive, etc.

Remote agents also belong to this outer layer. They are affected by tourism activity but can hardly affect it due to their limited resources. Usually, locals are considered remote agents, but they need to be brought closer to the center of the ecosystem to build a stronger destination identity and accomplish multidimensional sustainability. This does not only concern residents but also the workforce and beneficiaries of tourism. The local community uses the same resources as tourists – not only for tourism but particularly for recreation; thus, it could be considered a consumer segment.

Outside of the ecosystem remain the irrelevant agents – unwilling to cooperate or lacking resources and interest to participate in the health and recreation tourism product. They might represent parts of the tourism and healthcare industries or other local actors without relevancy to the destination ecosystem.

The total product of the destination can only be produced with the awareness of the participation of all layer actors.

Discussion and Implications

The main contributions of the proposed model of a health and recreational tourism destination are in the concretization of the business ecosystem model in the destination context and in including the characteristics of health and recreational tourism. This model is, however, only theoretical; it should be refined for different subtypes of health and/or recreational tourism and empirically validated by the mix of agents, products, and factors of specific destinations. Only in this way, it could indeed benefit the strategic management in practice.

While this paper is mainly focused on positioning the various agents of the health and recreational tourism destination ecosystem, there are many other socio-economic aspects of the interplay of these agents that still need to be investigated, e.g., the self-emergence of the ecosystemic structure, the motivation for participation related to the specific common value aimed by the agents, the settings of competition, the resilience, and self-evolution of the ecosystem, the concrete contribution of the ecosystem to sustainability and other complex goals. Hence, the proposed initial model is only the first step towards ecosystemic governance of the health and recreational tourism ecosystem.

It has not been among the purposes of this study to clarify the distinction between the different branches of health and recreational tourism; however, the reviewed literature indicates that these partially overlapping forms of tourism are defined too ambiguously, which prevents clear conceptual models and managerial practices to be created and development to be focused on each type instead of each case or destination. Overcoming this fragmentation would benefit the dialogue and synergies between destinations, promoting mutual understanding, exchange of good practices, convergence of management approaches, higher quality of the tourism products, and leading ultimately to higher visitor satisfaction.

References

Ahtiainen, A., Piirainen, A., & Vehmas, H. (2015). The essence of wellbeing tourism – case Peurunka. Matkailututkimus, 11(1), 26–42. https://journal.fi/matkailututkimus/article/view/90915

Albuquerque, H., Ferreira da Silva, A. M., Martins, F., & Costa, C. (2018). Wellness tourism as a complementary activity in saltpans regeneration. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 56-68). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

Baggio, R. (2008). Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tourism Analysis, 13(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354208784548797

Basole, R. C. (2009). Structural analysis and visualization of ecosystems: a study of mobile device platforms. AMCIS 2009 Proceedings. 292.

Bishop, M. V., Ólafsdóttir, R., & Árnason, Þ. (2022). Tourism, recreation and wilderness: public perceptions of conservation and access in the Central Highland of Iceland. Land, 11, 242, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020242

Björk, P., & Virtanen, H. (2005). What tourism project managers need to know about co‐operation facilitators. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 5(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250510014354

Bogomolova, E., & Dovlatova, A. (2019). Recreational tourism as a growth driver for tourist destination. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Economy, Judicature, Administration and Humanitarian Projects (JAHP 2019), 263–266. https://doi.org/10.2991/jahp-19.2019.57

Brawn, P. (2005). The importance of value chains, networks and cooperation as divers for SMEs’ growth, performance and competitiveness in the tourism-related industries. Proceedings of the Conference on Global Tourism Growth: A Challenge for SMEs (pp. 2-11).

Buonincontri, P., Morvillo, A., Okumus, F., & van Niekerk, M. (2017). Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: empirical findings from Naples. Tourism Management, 62, 264–277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.14

Cavicchi, A., Frontoni, E., Pierdicca, R, Rinaldi, C., Bertella, G. & Santini, C. (2018). Participatory location-based learning and ICT as tools to increase international reputation of a wellbeing destination in rural areas: a case study. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 82-94). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N., & Huan, T. C. (2008). Determining the motivation of wellness travelers. Anatolia, 19(1), 103–115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2008.9687056

Cherian, B., & Benfield, J. A. (2018). A dynamic view of visitors: the impact of others on recreation and restorative nature experiences. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 203-213). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

Cracknell, D. L., Pahl, S., White, M. P., & Depledge, M. H. (2018). The potential role of public aquaria in human health and wellbeing. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 178-189). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

Csrimaz, É., & Pető, K. (2015). International trends in recreational and wellness tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance, 32, 755–762.

Davchev, A. (2014). Управление на уелнес процесите в България [Management of wellness processes in Bulgaria]. Scientific Research of the Union of Scientists in Bulgaria-Plovdiv, А(I), 72–76.

den Hartigh, E., & Van Asseldonk, T. (2004). Business ecosystems: a research framework for investigating the relation between network structure, firm strategy, and the pattern of innovation diffusion. ECCON 2004 Annual meeting.

Derriks, T. (2018). Reinventing coastal health tourism through lifestyle sports: the complexities of kiteboarding in practice. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas, (pp. 138-148). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

De Tommassi, M., Cisternino, V., & Corallo, A. (2005). A rule-based and computation-independent business modelling language for digital business ecosystems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3681, 134–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/11552413_20

Deonarain, M., & Rampersad, R. (2024). Encouraging intersectoral collaboration to promote medical tourism in South Africa. Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism Research, 7(1), 434–442. https://doi.org/10.34190/ictr.7.1.1995

Georgiev, G., & Vasileva, M. (2009). Integration of health-oriented industries (balneology, spa, and wellness) in the scope of Bulgarian tourism. Икономика и управление [Economics and Management], 5(4), 56–62.

Gjorgievski, M., Kozuharov, S., & Nakovski, D. (2013). Typology of recreational-tourism resources as an important element of the tourist offer. UTMS Journal of Economics, 4(1), 53–60. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/105321

Grénman, M., & Räikkönen, J. (2015). Well-being and wellness tourism – Same, same but different? Conceptual discussions and empirical evidence. Matkailututkimus, 11(1), 7–25. https://journal.fi/matkailututkimus/article/view/90914

Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2006). The geography of tourism and recreation: Environment, place and space (3rd ed). Routledge.

Halme, M. (2001). Learning for sustainable development in tourism networks. Business Strategy and the Environment, 10(2), 100–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bse.278

Hansen, A. S. (2018). The visitor: connecting health, wellbeing and the natural environment. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 125-137). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0082

Henche, B. G., Salvaj, E., & Cuesta-Valiño, P. (2020). A sustainable management model for cultural creative tourism ecosystems. Sustainability, 12, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229554

Hillebrand, B. (2022). An ecosystem perspective on tourism: the implications for tourism organizations. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2518

Hjalager, A. M., Konu, H., Huijbens, E. H., Bjork, P., Flagestad, A., Nordin, S., & Tuohino, A. (2011). Innovating and re-branding Nordic wellbeing tourism. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Hojcska, Á. E. (2023). Place and role of medicinal water treatment services in health tourism. In T. Csákvári & Z. Varga (Eds.), Proceedings of VI. International Health Tourism Conference of Zalaegerszeg (pp. 49-61) Pécs, Hungary.

Horváth, A. (2023). Health resorts in tourism of Eastern Transylvania. In T. Csákvári & Z. Varga (Eds.) Proceedings of VI. International Health Tourism Conference of Zalaegerszeg (pp. 62-75). Pécs, Hungary.

Hristov, L. (2011). Cultural ecology and alternative tourism. Екологизация – 2011 [Ecologization – 2011], 32–37.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004a). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82(3), 68. https://hbr.org/2004/03/strategy-as-ecology

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004b). The keystone advantage: what the new dynamics of business ecosystem mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard business school press.

Iyer, B., Lee, C. H., & Venkareaman, N. (2006). Managing in a small world ecosystem: some lessons from the software sector. California Management Review, 48(3), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166348

Konu, H., Tuohino, A., & Björk, P. (2011). Wellbeing tourism in Finland: Finland as a competitive tourism destination. University of Eastern Finland – Centre for Tourism Studies.

Kostova, V. (2014). Tourism in rural areas. Интелигентна специализация на България – МВБУ Ботевград [Intelligent Specialization of Bulgaria – MVBU Botevgrad], 832–846.

Kylänen, M., & Rusko R. (2011). Unintentional coopetition in the service industries: the case of Pyhä-Luosto tourism destination in the Finnish Lapland. European Management Journal, 29(3), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.10.006

Langvinienė, N. (2014). Changing patterns in the health tourism services sector in Lithuania. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156, 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.194

Lee, C. F. (2016). The factor structure of tourist satisfaction in forest recreation tourism: the case of Taiwan. Tourism Analysis, 21, 251–266. http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/108354215X14400815080442

Liao, C., Zuo, Y., Xu, S., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2023). Dimensions of the health benefits of wellness tourism: a review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1071578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1071578

Lindell, L., Dziadkiewicz, A., Sattari, S., Misiune, I., Pereira, P., & Granbom, A. (2019). Wellbeing tourism and its potential in case regions of the South Baltic: Lithuania – Poland – Sweden. Linaeus University.

Lück, M., & Aquino, R. S. (2021). Domestic nature-based tourism and wellbeing: a roadmap for the new normal? In J. Wilks, D. Pendergast, P. A. Leggat & D. Morgan (Eds.), Tourist health, safety and wellbeing in the new normal, 269–292. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5415-2_11

March, R., & Wilkinson, I. (2009). Conceptual tools for evaluating tourism partnerships. Tourism Management, 30(3), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.09.001

McKercher, B. (1996). Differences between tourism and recreation in parks. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(3), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383%2896%2900002-3

Merdivenci, F., & Karakaş, H. (2020). Analysis of factors affecting health tourism performance using fuzzy DEMATEL method. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 8(2), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.30519/ahtr.734339

Mihaylov, М. (2012). Здравен туризъм–профилактични и терапевтични аспекти [Health tourism – preventive and therapeutic aspects].

Milwood, P. A., & Crick, A. P. (2021). Culinary tourism and post-pandemic travel: Ecosystem responses to an external shock. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 7(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4516562

Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–86. https://hbr.org/1993/05/predators-and-prey-a-new-ecology-of-competition

Moore, J. F. (1996). The death of competition: leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystems. Wiley Harper Business.

Moore, J. F. (1998). The rise of a new corporate form. Washington quarterly, 21(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/01636609809550301

Nokkala, L. (2023). Digitaalinen opas Helsingin puutarhakohteisiin [Digital guide to Helsinki's garden destinations]. LAB University of Applied Sciences. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2023112331118

Palancsa, A. (2023). Where is health tourism going? In T. Csákvári & Z. Varga (Eds.), Proceedings of VI. International Health Tourism Conference of Zalaegerszeg (pp. 134-144). Pécs, Hungary.

Palkovics K., & Varga, Z. (2023). The situation of wellness hotels in Hungary in the light of Covid. In T. Csákvári & Z. Varga (Eds.), Proceedings of VI. International Health Tourism Conference of Zalaegerszeg (pp. 218-228). Pécs, Hungary.

Peltoniemi, M., & Vuori, E. (2005). Business ecosystem as a new approach to complex adaptive business environments. Frontier of e-business research, Tampere, Finland.

Quintela, J. A., Costa, C., & Correia, A. (2016). Health, wellness and medical tourism – a conceptual approach. In J. Álvarez-García & M. C. Del Río Rama (Eds.), Enlightening tourism. A pathmaking journal, (6)1. Special issue on “Thermal tourism, thalassotherapy and spas: the water in the health and wellness tourism” (pp. 1-18).

Richards, G., & Hall, D. (Eds.) (2002). The community: a sustainable concept in tourism development? Tourism and sustainable community development (pp. 1-14). Routlege.

Selen, W., & Ogulin, R. (2015). Strategic alignment across a tourism business ecosystem. Athens Journal of Tourism, 2(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajt.2-3-3

Scott, D., de Freitas, C., & Matzarakiz, A. (2009). Adaptation in the tourism and recreation sector. In Ebi, K.L., Burton, I. & McGregor, G.R. (Eds.) Biometeorology for adaptation to climate variability and change, (pp. 171-194). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8921-3_8http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8921-3_8

Scott, N., Baggio, R., & Cooper, C. (2009). Network analysis and tourism: from theory to practice. Aspects of tourism, 35. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845410896

Smith, M. K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of tourism research, 66, 1–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

Smith, M., & Puczkó, L. (2008). Health and wellness tourism. Butterworth-Heinemann. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780080942032

Smith, M., & Puczkó, L. (2014). Future trends and predictions. In M. Smith & L. Puczkó (Eds.) Health, tourism, and hospitality: spas, wellness and medical travel (2nd ed) (pp. 203-227). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203083772

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Spigel, B. (2015). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

Steckenbauer, G. C., Tischler, S., Hartl, A., & Pichler, C. (2018). A model for developing evidence-based health tourism: the case of ‘alpine health region Salzburg, Austria’. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 69-81). http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0069

Szymańska, E. (2015). Construction of the model of health tourism innovativeness. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213, 1008–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.518

Taff, B. D., Benfield, J., Miller, Z. D., D’Antonio, A., & Schwartz, F. (2019). The role of tourism impacts on cultural ecosystem services. Environments, 6(43). https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6040043

Thomas, L. D. W., & Autio, E. (2012). Modeling the ecosystem: a meta-synthesis of ecosystem and related literatures (pp. 1-27). DRIUD Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Toksöz, Ö. (2021). Factors affecting health tourism and management of health tourism. TURAN-CSR, 13(50), 207–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.15189/1308-8041

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4, 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Tribe, J. (2004). The economics of recreation, leisure and tourism (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

Ullah, N., Zada, S., Siddique, M. A., Hu, Y., Han, H., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. (2021). Driving factors of the health and wellness tourism industry: a sharing economy perspective evidence from KPK Pakistan. Sustainability, 13, 13344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313344

Varga, Z., & Csákvári, T. (2019). Recreational tourism in West-Hungary. Köztes-Europa, 11(1), 25, 115–125.

Varga, Z., Juhász, E., Boncz, I., & Komáromy M. (2018). Consumer survey of health and recreational tourism in the West-Transdanubian region of Hungary. Value in Health, 21(3), S322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.09.1921

Voigt, C., Brown, G., & Howat, G. (2011). Wellness tourists: in search of transformation. Tourism Review, 66(1/2),16–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/16605371111127206

Wagenaar, M., & Vaandrager, L. (2018). Experiencing a water sports holiday as part of a rehabilitation trajectory: identifying the salutogenic mechanisms. In I. Azara, E. Michopoulou, F. Niccolini, B. D. Taff & A. Clarke (Eds.), Tourism, health, wellbeing and protected areas (pp. 167-177.) https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391315.0167

Wang, Y., Wang, L., Zhou, W., & Ying, Q. (2023). Rural recreation tourism in the Panxi region of China in the context of ecological welfare. Heliyon, 9, e22384, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22384

Yanakieva, A., & Karadzhova, Z. (2020). Профил на потребителя на продукта на здравния туризъм [Health tourism product user profile]. Research Papers of UNWE, 5, 31–42.

Zhong, L., Deng, B., Morrison, A. M., Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., & Yang, L. (2021). Medical, health and wellness tourism research – a review of the literature (1970-2020) and research agenda. Internal Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 10875, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010875

Download Count : 47

Visit Count : 113

Keywords

Tourism Destination Governance; Business Ecosystem; Health Tourism; Recreational Tourism

How to cite this article:

Röntynen, R. (2024). First steps towards ecosystemic governance for health and recreational tourism destinations. European Journal of Studies in Management and Business, 31, 64-79. https://doi.org/10.32038/mbrq.2024.31.05

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interests

No, there are no conflicting interests.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/