Original Research

Supporting Cooperation between Supply Chain Members Through a Combination of Soft and Hard Coordination Tools

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

One of the most important tasks of supply chain management is to ensure that members cooperate properly. It is necessary to integrate value-adding processes, as this is the only way to maintain a high level of customer service. This is the way to create the value that the final customer will pay for and have his needs fully met. However, the question arises: do all companies really want to cooperate with each other at a high level? Alternatively, the question can be looked at from another angle: do all the links in the chain need to cooperate at a high level? The aim of this study is to examine to what extent corporate attitudes influence the form and extent of cooperation. To this end, the paper examines the use of contracting, one of the most popular instruments in the supply chain management literature. Using a case study, the result of the study is a composition matrix that shows the relationship between the preferred form of collaboration of companies and the contracts that best support this. To do this, it is first necessary to identify the possible forms of cooperation and their characteristics, after which the contracts and their conditions and characteristics of application must be understood. By putting the two pieces of information together, a matrix can be created, which can be used to recommend the most appropriate contract for the relationship that best matches the company's attitudes to improve cooperation and coordination between the members.

Tamás Faludi

University of Miskolc, Faculty of Economics, Institute of Management Sciences Miskolc, Hungary

Abstract

One of the most important tasks of supply chain management is to ensure that members cooperate properly. It is necessary to integrate value-adding processes, as this is the only way to maintain a high level of customer service. This is the way to create the value that the final customer will pay for and have his needs fully met. However, the question arises: do all companies really want to cooperate with each other at a high level? Alternatively, the question can be looked at from another angle: do all the links in the chain need to cooperate at a high level? The aim of this study is to examine to what extent corporate attitudes influence the form and extent of cooperation. To this end, the paper examines the use of contracting, one of the most popular instruments in the supply chain management literature. Using a case study, the result of the study is a composition matrix that shows the relationship between the preferred form of collaboration of companies and the contracts that best support this. To do this, it is first necessary to identify the possible forms of cooperation and their characteristics, after which the contracts and their conditions and characteristics of application must be understood. By putting the two pieces of information together, a matrix can be created, which can be used to recommend the most appropriate contract for the relationship that best matches the company's attitudes to improve cooperation and coordination between the members.

The Need for Supply Chain Coordination

Supply chains have evolved a lot in recent times. Since the 1990s, the number of supply chain members has been steadily increasing. This results from the decline of mass production, which has been replaced by demand-driven production (Sindi & Roe, 2017). This requires a better understanding of customer needs, which have become increasingly fast and dynamic with the emergence of a consumer society. This was partly due to globalisation, i.e. companies entered the international arena, boosted international trade and made products available that were not available before globalisation, and still are today. Another reason is that more and more companies have outsourced certain processes. This has led to the development of a whole service industry, with the emergence of various financial, financing and logistics service companies (Langley et al., 2016). These organisations are all embedded in supply chains. From the turn of the millennium onwards, supply chains became more and more numerous, and supply chains became more and more diversified. Foreign suppliers, customers, and subsidiaries built according to economic criteria could be located on other continents. And as IT evolves, companies have a growing set of tools at their disposal to ensure virtual connectivity (Frazzon et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2022; Samper et al., 2022).

It can be seen that coordinating the processes of the members in supply chains with such a large number of members has become a difficult task. The literature no longer even defines these supply chains as chains; many researchers refer to supply chains as supply networks. The efficient and effective functioning of such a network is very difficult to ensure and maintain. There are many factors that hinder proper collaboration, ranging from different organisational structures and cultures to different organisational goals, to differences in lead times, delivery times, ordering and production schedules, and ordering and production quantities (Arshinder et al., 2005; Corallo et al., 2020; Yin, 2021). These processes, in turn, contribute greatly to achieving customer satisfaction and raising service levels.

For these reasons, the issue of supply chain coordination, i.e. the harmonisation of the processes of supply chain actors, has been raised. Supply chain coordination aims to support the cooperation of its members. This should cover all processes that directly or indirectly create value for the customer. In order to align processes, supply chain coordination offers tools to reduce information asymmetries and conflicts of interest between members and can also help to align objectives (De Giovanni, 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Um & Kim, 2019; Xue et al., 2022). Without coordination, uncertainty within the chain will increase, which will provide the basis for poor decisions. For example, if this uncertainty relates to demand, which means that there is insufficient quantity and quality of information available to decision makers, then, due to the rational behaviour of chain members, they will try to compensate for demand uncertainty by accumulating stocks. This is due to the focus on the next chain, and only based on the needs of the immediate chain members will the organisation make decisions. It will, therefore, hold enough stock to ensure that it can meet demand. This uncertainty can spill over into the entire chain or network (Ponte et al., 2020; Wang & Disney, 2016). This may increase costs, reduce capacity utilisation and, therefore, reduce the efficiency and effectiveness of the operation, which may affect the whole network.

It can, therefore, be seen that supply chain coordination is an area with complex tasks. Early research has identified coordination as the sharing of resources (Narus & Anderson, 1996). Over time, coordination has been approached from a different perspective, focusing on coordinated planning, development and information sharing (Larsen, 2000). The 2000s brought a further broadening of perspectives on the subject – now shared decision-making mechanisms and the sharing of profits are also included in the coordination issue (Hill & Omar, 2006). The market environment changes of the 2010s, with dynamically changing customer demands and changing consumer behaviour, have brought new challenges for coordination. The primary objective has become to manage and resolve conflicts of interest between firms, which facilitates effective collaboration between firms, supporting organisations and their supply chains to respond effectively and quickly to rapidly changing market environments and customer needs (Balakrishnan & Geunes, 2009; Holweg & Pil, 2008). This has become one of the major challenges of supply chain coordination: how to align the processes of non-cooperative actors, encourage cooperation, and reduce conflicts of interest to better meet the ever-changing market needs (Singh, 2011). Without coordination, the members would be lost in the chain, and the right information would not get through, which also affects the flow of material. For example, logistical principles may be compromised, i.e., the customer will be dissatisfied if the wrong material is received, or not in the right quantity or quality. If the needs are not known precisely by the members, it is easy for organisations to build up stocks or to have insufficient material to meet customer needs. In both cases, there can be a serious increase in costs and more serious consequences, such as loss of partners, which can lead to a reduction in profits. The key objective of supply chain coordination is to avoid these consequences, supported by advances in technology, as more and more tools are available to collaborate and coordinate processes effectively (Khan et al., 2022; Mastos et al., 2021; Witkowski, 2017).

Overall, supply chain coordination is a concept with the ultimate goal of improving the performance of the entire supply chain. To achieve this, it requires effective coordination of cooperation between members, integration of processes to achieve common goals and alignment of planning processes to achieve these goals.

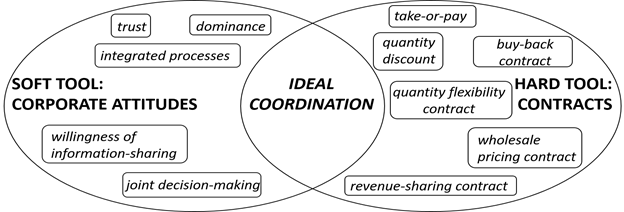

The literature gives different interpretations of the tools that can be used in supply chain coordination. This paper follows the concept that there are soft and hard factors at the disposal of coordination mechanisms. Soft factors are interpreted from a behavioural perspective, i.e., factors that include the organization's characteristics, its attitude towards cooperation, the existence and extent of trust and related factors. So soft factors are, in fact, those factors that show the extent to which the company wants to cooperate. Hard factors are the financial framework of cooperation and the conditions that will provide the framework for the partnership (Hertz & Alfredsson, 2003; Singh & Benyoucef, 2013).

The article assumes that coordination between the two groups is necessary to achieve the right level of coordination. In the next chapter, the paper will look at the forms of cooperation between firms within the soft factors and then examine the possibility of coordination through contracts within the hard factors.

Forms of Cooperation Between Companies

Supply chains are characterised by the need for their members to work together to meet the final consumer needs. However, competition dictates the opposite since a company can only gain a competitive advantage if it is better at something or has some extra information that can give it an edge over the others. For this reason, the concept has evolved, and the members of the chain are forced to work together even in such a competitive situation. This is called coopetition (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014; Manzhynksi & Biedenbach, 2023). In the 21st century, it is not members but supply chains that compete with each other, and cooperation within chains has become more important.

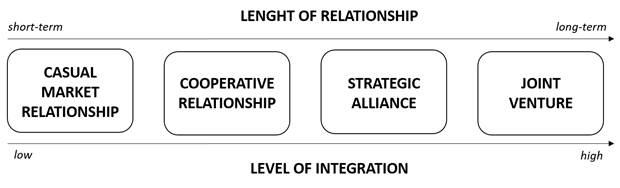

For the supply chain to function effectively, it is essential to establish some degree of partnership between its members. The extent of the relationship is a function of the trust between the members (Capaldo & Giannoccaro, 2015; Fu et al., 2022; Paluri & Mishal, 2020). These can be used to typify the forms of the partnerships between the members. If this trust is low, or if the type of transaction does not require a deeper relationship, even of a strategic nature, we can speak of a casual market relationship. This relationship may occur with a member buying or selling a product with whom the partner has only occasional contact, is not typical for a high-value commodity or is not typical for a partner supplying a commodity of strategic importance. We speak of a cooperative relationship when there is already minimal information sharing, a short-term relationship. It should be used with a partner supplying materials who is a recurring partner, not a high-value commodity and not a strategically important material. Strategic alliances are collaborations that require a higher level of integration, where a common goal is shared between the collaborating parties with the resources needed to achieve that goal. This relationship should be with a partner who supplies materials that are absolutely necessary for the operation, even if a daily supply of the material is required so that it does not deal with a very important and relatively high-value commodity. This relationship should be with a partner who supplies materials that are absolutely necessary for the operation; even a daily supply of the material is required so that you are not dealing with a very important and relatively high-value commodity. Thus, trust and information sharing, and risk-taking are at a high level between the parties opting for such cooperation. Higher levels of cooperation are joint ventures and mergers, which are another form of cooperation, as a new entity with legal personality is created, or in the latter case, one company merges with another (Besanko et al., 2004; Kraljic, 1983).

Figure 1 shows a summary of the forms of cooperation, with a description of their degree of integration. The latter two cases are very extreme for the purposes of this research and will not be examined further in this paper.

It is clear that trust is one of the foundations on which the degree of partnership between the parties involved is based. Since the emergence of strategic alliances in the 1990s, there has been an increasing trend in research on the concept of trust (Michalski et al., 2019; Sahay, 2003; Tejpal et al., 2013; Uca et al., 2017). This trust will also influence the quality of information flows, believing that higher trust means a higher willingness to share information.

Forms of Cooperation Based on the Need for Integration (own construction)

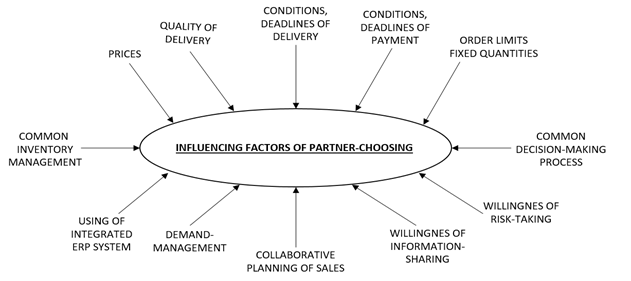

As chains are nowadays networked, it is very important that the choice of partner and the form of cooperation is not unconceived. This is, of course, influenced by basic partner selection factors, such as price, payment terms, delivery conditions, and now the trust factor. However, it is also necessary to consider the type of material the supplier supplies or the type of material we supply to our customers, as these can determine the type and depth of the relationship required, thus avoiding the pitfalls of partner selection. According to the Krajlic matrix, one should also take into account the ease of obtaining the material, the size of the market, and the value of the material to the company (Kraljic, 1983). In my opinion, this factor should not be overlooked either, as it is worthwhile to have a long-term contract with a partner that supplies material of strategic importance to the company. Moreover, if a form of cooperation is not chosen that is in line with the company's attitude, the relationship will not work effectively, so the soft factors of partner selection must also be taken into account. It is, therefore, worth examining what expectations and needs the organisation has of the prospective partner and what time horizon and depth of cooperation is preferred. If these attitudes and characteristics are known, the choice between contracts can be facilitated.

Contracts within the Supply Chain

There is a large literature on contracts that can be used for supply chain coordination. In principle, it is worth clarifying how contracts that can be used within supply chains are to be interpreted (Table 1).

A Summary of the Interpretation of Contracts in Literature

|

AUTHOR(S) |

RESULTS |

|

Contracts must be profitable, fair, flexible and workable for both parties |

|

|

There is no clear definition; it should be identified by its coordination capacity and the benefit it provides |

|

|

Sharing the partners' risks, costs and revenues is at the heart of contracts |

|

|

Contracts aim to improve the performance of supply chains |

|

|

Contracts define the obligations of the parties and the allocation of risks and costs between them |

Table 1 summarises the findings of relevant researchers on the interpretation of contracts. Many common points can be found in the approaches and definitions. From the 2020s onwards, there has not really been any new approach to the subject. Overall, it can be concluded that contracts provide a framework for cooperation, with the universal aim of improving the performance of organisations and the supply chain as a whole. Contracts thus set out the proportions of risk, cost, and revenue sharing, which should also result in members being able to cooperate under controlled conditions.

A brief description of the most common contracts in the literature follows. These contracts are wholesale pricing, take-or-pay, quantity discount, quantity flexible pricing, buy-back contracts, and revenue-sharing contracts.

When using contracts, it must be specified whether the chain is centralised or decentralised. These two arrangements, in fact, represent the degree of cooperation. In a centralised arrangement, vertical integration of the partners is achieved, i.e. the different value-creating processes are interconnected. The members seek to cooperate, and by putting conflicts of interest to one side, the parties tend to define and achieve a common goal. In a decentralised case, however, the members behave in the opposite way. They put cooperation on the backburner in pursuit of their own interests and profit-maximising goals, thus creating a less cooperative or in some cases, non-cooperative relationship (Cai et al., 2020; Giannoccaro, 2018).

In the case of wholesale pricing, the seller unilaterally determines the unit price that can be applied between members, and the buyer orders the quantity that suits him. This mechanism is typical in decentralised arrangements, while in centralised arrangements, prices are set to suit both parties so that lower prices can be expected. In this centralised case, the members cooperate at a high level, define common objectives, and achieve vertical integration. In the decentralised case, however, members only have their own interests in mind, so the level of cooperation is low or even non-existent (Giannoccaro, 2018; Tantiwattanakul & Dumrongsiri, 2019; Vipin & Amit, 2021).

A take-or-pay contract is applicable in a monopoly market. It is a type where the seller unilaterally determines the prices that can be applied between members and the quantities that can be sold. If the buyer accepts these conditions, he receives the goods. Since there are either very few alternatives or none at all, if the buyer does not accept the terms, the buyer is unlikely to get the goods or services. It does not promote cooperation but only formalises the transactions of monopolistic market players (Johnston et al., 2008).

A quantity discount is a type of sales incentive, where the more the customer buys, the lower the price he can get. There is an inverse proportionality between the quantity sold and the prices between the parties. Prices and discount rates will often be unilaterally set by the seller and, therefore, not necessarily conducive to cooperation. However, repeated re-purchases can already trigger an increase in the trust factor, which can later have a beneficial effect on the cooperation of the members (Huang et al., 2020; Ponte et al., 2020).

With a quantity flexibility contract, order lot sizes can be adjusted according to fluctuations in demand. This requires the definition of a lower and an upper order limit, which can be developed on the basis of a longer-term demand forecast. This type of price fixing already supports cooperation and the development of longer-term cooperation on this basis. In some cases, there is a positive situation in which the longer the contract term, the more flexibility in the quantity that can be ordered and the associated concessions (Heydari et al., 2020; Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021).

Under a buy-back contract, the seller guarantees to buy the buyer's remaining unsold stock at a predetermined price. This makes it an option for parties with a high-risk appetite, as this new type of price represents a high risk for the parties. The main problem is the determination of the buy-back price. This requires a higher level of cooperation between the parties, as joint decision-making processes are inevitable (Vipin & Amit, 2021).

Under a revenue-sharing contract, the revenue of the member closest to the final consumer is distributed to the other members of the chain in a predetermined proportion. This gives the last member an incentive to sell as much as possible, as this is how he or she will get a higher share of the revenue. However, the additional revenue may keep the prices applicable between the parties in the chain low. A problem may arise in the determination of the sales ratios, which should reflect the roles in the chain; otherwise, the allocation will not be fair. The application of this contract requires a very high level of cooperation (Huang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022).

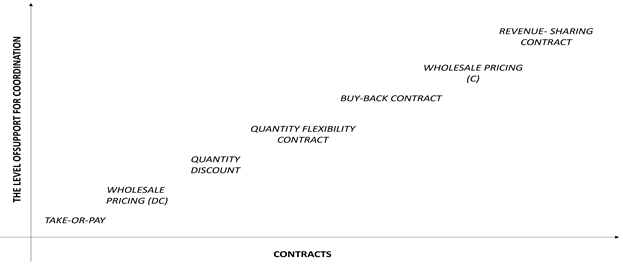

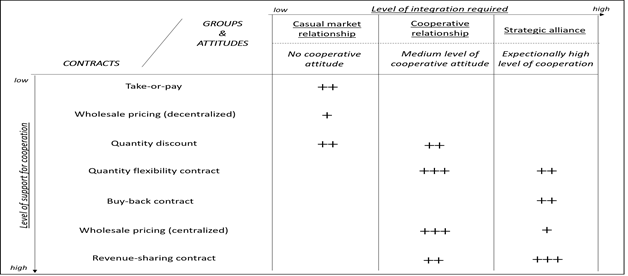

The Possibility of Grouping Types of Contracts According to Their Degree of Support for Cooperation

Figure 2 summarises the contracts examined. It can be seen that some contracts are less conducive to higher levels of integration – these contracts are used to coordinate short-term relationships and less complex cooperation. While some contracts require a high level of integration and, thus, cooperation between partners.

Case Study

I would like to illustrate the applicability of the model with a practical study. Since theoretical studies and results often remain theoretical and have few or only strong limitations in practical application, I consider it important to illustrate the research results with a practical, case study example.

Research Structure and Sample

For a practical approach, I conducted empirical research in Hungary. Since the range of contracts that can be effectively used in certain circumstances is already known, my purpose is to investigate how partner selection factors appear in practice and how strongly they can influence the organisation in a partner selection situation. The goal of my research is to be able to typify corporate attitudes based on partner selection factors and to match the preferred form of cooperation with the most appropriate contract. The expected result is the creation of a proposal system.

The empirical research was carried out within the framework of the preparation of my doctoral thesis. The research was conducted online, anonymously, in strict compliance with GDPR principles.

I was given a sample of nearly 98 respondents, mainly small and medium-sized enterprises in Hungary. Most of these companies work in the manufacturing sector and are also involved in international trade. The respondents were mainly located on the manufacturing side of the supply chain. Five scale questions were used to assess the extent to which respondents considered the defined partner selection factors to be important influencing factors (Figure 3).

The Partner Selection Factors

The results were analysed by cluster analysis. My aim is to explore whether clustering is possible based on the strength of the influence of partner choice factors. If the value of factors that support cooperation is higher, then the respondent organization will likely prefer a higher level of partnering.

Results

The results of the cluster analysis show that there is a differentiation between the companies in the sample based on the strength of the partner selection factors, but there are common points across the groups.

In all groups, price is a very important partner selection factor, and delivery and payment terms and deadlines are also highly relevant, but there are differences between the groups. This was an expected result, as it is primarily the information that is important to the organisations, with price being the most important filter.

So, the first result of the research is that price is always an important factor in partner selection, regardless of the level of cooperation.

The cluster analysis distinguished three broad groups. For the partner selection factors, I considered factors 4 and 5 as having a high power of influence, 3 as having a medium power of influence and 2 and 1 as weak.

Group 1 is a group of respondents who attach great importance to the use of an integrated ERP system, preferring common decision making processes, including common sales planning, demand management, and inventory management. The members of the group should have a high-risk appetite, but this is shared between the members. Group 1 respondents are also characterised by a high level of information sharing, which they expect from themselves and from the potential partner. Setting and respecting order limits is also important for the group. This group has and expects a high trust factor from their partner. This group may be made up of companies that work with partners that supply higher-value, strategically important material. The nature of the relationship required is thus medium to long term with a high level of integration. Of the partnerships defined, the most appropriate form for the group is a strategic alliance or a higher level of integration (for example, a joint venture).

For group 2, integration is less important, but the desire to cooperate still appears in the answers. Joint decision making, joint sales planning, joint demand management and inventory management are of medium importance, and thus the operation of an ERP system that integrates the companies is also not expected. The willingness to take risks and share information is also a medium. Delivery conditions are a less important factor, as is the setting of order limits. This is presumably due to the lower level of cooperation, which makes it less relevant to set order limits. The nature of the relationship required is thus medium to short term with low levels of integration. The use of common resources can be assumed, but their share and extent is severely limited. Respondents present a picture of a partnership that acquires large volumes of goods from a market where there are, in turn, many other similar partners. Thus, of the partnerships defined, the one that best fits the group is the cooperative relationship.

Group 3 shows a downward trend in the need for integration. The value of joint decision making, joint demand and inventory management and joint sales planning is particularly weak, which means that the members do not require them of the group. Accordingly, the willingness to share information and take risks is low. However, integrated ERP is still considered relatively important. It is interesting to note that for this group, price scored an average of 4, which is still considered an important factor, but payment and delivery terms and tied order quantities scored medium or below. As they are assumed to have no influence in shaping these factors, they may not be an important partner selection factor. This may be the case for partners who, due to the nature of the goods, have only occasional and infrequent contact with the organisation. Therefore, Group 3 does not seek to establish a long-term relationship. It may be a partnership between companies supplying products that are routine, low value, high variety suppliers. Thus, price will be the main consideration if they do not plan for the long term. The time required for the required relationship is short-term or occasional. Of the partnerships defined, the form that best fits the group is the casual market relationship. The characteristics of the identified groups are summarised in Table 2.

A Summary of the Response of the Identified Groups in Percentage Form [including only the 4 and 5 value]

|

|

|

Group 1. |

Group 2. |

Group 3. |

|

Prices |

91.18 |

89.19 |

77.78 |

|

|

Quality Of Delivery |

.100 |

89.19 |

70.37 |

|

|

Conditions, Deadlines Of Delivery |

91.18 |

78.38 |

62.96 |

|

|

Conditions, Deadlines Of Payment |

91.18 |

83.78 |

48.15 |

|

|

Order Limits, Fixed Quantities |

76.47 |

48.65 |

25.93 |

|

|

Common Decision-Making Process |

91.18 |

37.84 |

14.81 |

|

|

Common Sales Planning |

67.65 |

13.51 |

3.7 |

|

|

Common Demand Management |

73.53 |

24.32 |

22.22 |

|

|

Common Inventory Management |

64.71 |

21.62 |

3.7 |

|

|

Willingness Of Risk-Taking |

82.35 |

59.46 |

25.93 |

|

|

Willingness Of Information-Sharing |

94.12 |

48.65 |

11.11 |

|

|

Using Of Integrated Erp System |

82.35 |

45.95 |

51.85 |

|

Table 2 is a good illustration of how the need for integration is reduced in groups. While Group 1 explicitly requires integrated activities, this need almost disappears in Group 3. An interesting result is that the price level was also an important factor in almost 78% of cases. This result suggests that Group 3 may have been formed by firms in a chain or downstream that do not have much influence on price developments; they are players in a market where prices are given and this set of players has less influence. In addition to this result, it can be seen that the influence of the various joint activities is very low, which leads to the conclusion that the companies in Group 3 do not require joint processes and, therefore, do not plan to cooperate in the long term.

Setting up the Decision-support Model

The goal of the model is to create a decision support model that alleviates coordination problems, optimises, and takes into account the conditions for joint cooperation based on needs. The contracts preferred by the literature can provide a good solution to eliminate coordination problems, but it is essential to keep in mind the needs of the partners, i.e. the form of cooperation favoured by them based on organisational characteristics and corporate attitudes. After all, contracts can only work well if the parties choose and apply the contract that best suits their expectations, characteristics and attitudes in managing their relationship with the partner.

The identified partnerships can be assigned contracts based on their characteristics. A contract may support more than just one partnership, so it is also worth distinguishing the strength of the support (Table 3).

Notations Used by the Model

|

|

|

+ |

++ |

+++ |

|

Subscription |

Less Recommended |

Recommended |

Highly Recommended |

|

|

Meaning |

limited ability to coordinate the partnership |

handles coordination problems well |

minimises the coordination problems |

|

It is also worth considering if there is only minimal coordination between partners in a contract. In the case of a decentralised arrangement, even with a minimum of cooperation, it is worth using a contract, as this will make the partnership one step more organised – obviously, in this case, a contract should be chosen which does not aim at perfect integration. A "+" will be displayed in this case, indicating that the contract is only able to coordinate the given partnership to a minimum. The optimal case will be indicated by a "++" when the coordination problems can be sufficiently addressed by the contract. The contract best suited to a given cooperative relationship will be indicated by a '+++'; in this case, the contract will be able to support cooperation at a high level, minimising or even eliminating coordination obstacles.

After having studied the contracts and partner relationships and using the practical responses of the companies in the empirical research sample, the matrix can be developed as follows (Figure 4).

Contract-choosing Matrix

The use of contracts can pave the way for a higher level of cooperation and can even help to increase the trust factor. So, contracts can not only address current problems but should also be seen as an opportunity for a higher level of cooperation in the future. This is why it is worth differentiating between recommending and matching contracts in the decision-support system: if a relationship starts with a less recommended contract, it can easily switch to a more suitable contract later on. In this way, progress can be made within a partnership. The two axes of the matrix show the need for integration in the partnership and the extent to which contracts support cooperation. The higher the level of integration required from the partners' point of view, the higher the level of vertical integration supportive contracts should be chosen. The degree of vertical integration also differentiates the range of contracts that can be chosen.

As can be seen from the matrix, the highest level of integration is the revenue-sharing contract, which provides a high level of support for the creation of strategic alliances and an equally high level of coordination. Companies opting for this form of cooperation basically need a contract that allows for stronger integration between the members, as there is a high demand for information sharing, joint activities and joint decision-making mechanisms. Thus, in addition, a cooperative, centralised arrangement of wholesale pricing, even as an initial contract, which could later be replaced by a more serious type, could be a good way to improve coordination. Quantity flexibility contract is also a potential good solution, as the high level of information sharing allows for accurate demand forecasts and thus a good definition of the limits required for the contract.

Companies that require lower integration may prefer to choose unilateral contracts such as take-or-pay, quantity discounts or a traditional wholesale pricing contract. A take-or-pay contract is well suited to monopoly markets, and this monopoly nature may foreclose cooperation, but it may help to set the rules of the relationship in the longer term, which, although unilaterally determined by the seller, may help to facilitate transactions between the members. A quantity discount may also be a good choice because its repeated application can form the basis of a partnership. Wholesale pricing is also a type where a high level of integration is not required, but the rules of the relationship are sufficiently known to both parties.

For medium integration needs, quantity discounts or quantity flexible contract may also be an option. Wholesale pricing is also highly recommended. Although a quantity flexible contract is only an option if there is a higher level of trust between the parties due to the medium level of information sharing, wholesale pricing or quantity discounting could be considered as an initial contract. The use of these may act as a motivating force for the partners, as repeated use of these may lead to a relationship of trust between the partners, which may lead to a higher level of integration being required later. If this is achieved, a revenue-sharing contract can be offered to the members. With this contract, the parties can easily become strategic allies.

Limitations of the Model

An analysis of partner selection factors and their influence on the responses of Hungarian firms is limited. Thus, the results obtained in this research only refer to the sample, and it can only be assumed that similar results can be obtained in general. Future research objectives include extending the research sample, and international experience in the research would be needed to obtain more thorough results and thus to put the model developed on a more solid footing. In addition, in many cases, researchers experiment with combining individual contracts to create hybrid types. It is also worthwhile to include the study of these hybrid types in future research in order to broaden the range of contracts that can be offered. In addition, the research investigates the coordination of only two members. It would be worth extending this to supply chain stages or possibly the whole supply chain.

Conclusion

The matrix presented in this study could be a good basis for developing a decision support model to avoid the choice of a contract that does not fit the preferred cooperation relationship as a tool to improve coordination. However, the matrix can also be approached as a process of evolution of a cooperative relationship. Indeed, contracts may have the potential to increase trust and thereby change the attitudes of firms and thus achieve a higher level of integration. But until this happens, they are a perfect opportunity to address the current situation. If the preferences, characteristics and attitudes of the company are known, i.e. the extent to which they wish to establish a cooperative relationship with each partner, it is easy to offer them a contract that is adapted to the nature of the relationship and helps them to establish and operate their cooperation. It is, therefore, very important to know the soft factors within coordination. Each organisation will not wish to establish the same depth and duration of cooperation with each partner. This will shape the organisation's partner selection factors and their strength of influence. However, knowing these will make it easier to match the contract best suited to their preferences. Contracts are identified in the literature as hard factors, the main purpose of which is to define the framework for cooperation, exploit financing opportunities, lay down the rules for transactions between the parties, and define the sharing of risks, revenues and costs (Figure 5).

Combining Soft and Hard Tools to Achieve Ideal Coordination

Thus, it can be concluded that hard and soft factors must be coordinated in all ways for coordination to be effective. If this is not done, a contract may be selected that is less or not at all supportive of the relationship required. In this case, the use of contracts will have the opposite effect: they will not help, but rather will further undermine coordination between members.

References

Arshinder, Kanda, A., & Deshmukh, S. G. (2008). Supply chain coordination: Perspectives, empirical studies and research directions. International Journal of Production Economics, 115(2), 316–335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2008.05.011

Balakrishnan, A., & Geunes, J. (2009). Collaboration and Coordination in Supply Chain Management and E-Commerce. Production and Operations Management, 13(1), 1–2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2004.tb00140.x

Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition – quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.015

Besanko, D., Dravone, D., Shanley, M., & Schaefer, S. (2004). Economics of strategy. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Cachon, G. P. (2003). Supply chain coordination with contracts. Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, 11, 227–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-0507(03)11006-7

Cai, Y. J., Coi, T. S., & Zhang, J. (2020). Platform supported supply chain operations in the blockchain era: Supply chain contracting and moral hazards. Decisions Sciences, 52(4), 866–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12475

Capaldo, A., & Giannoccaro, I. (2015). How does trust affect performance in the supply chain? The moderating role of interdependence. International Journal of Production Economics, 166, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.04.008

Coltman, T., Bru, K., Perm-Ajchariyawong, N., Devinney, T. M., & Benito, G. R. (2009). Supply Chain Contract Evolution. European Management Journal, 27(6), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.11.005

Corallo, A., Latino, M. E., Menegoli, M., & Pontradolfo, P. (2020). A systematic literature review to explore traceability and lifecycle relationship. International Journal of Production Research, 58(15), 4789–4807. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1771455

De Giovanni, P. (2021). Smart supply chains with vendor managed inventory, coordination, and environmental performance. European Journal of Operational Research, 292(2), 515–531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2020.10.049

Frazzon, E. M., Rodriguez, C. M. T., Pereira, M. M., Pires, M. C., & Uhlmann, I. (2019). Towards Supply Chain Management 4.0. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 16(2), 180–191. http://dx.doi.org/10.14488/BJOPM.2019.v16.n2.a2

Fu, X., Tan, H., Tsenina, E., Liu, S., & Han, G. (2022). Information sharing based on two-way perceptions of trust and supply chain decisions: A simulation based approach. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2022.111938

Giannoccaro, I. (2018). Centralized vs. decentralized supply chains: The importance of decision maker’s cognitive ability and resistance to change. Industrial Marketing Management, 73, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.01.034

Hertz, S., & Alfredsson, M. (2003). Strategic development of third party logistics providers. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(2), 139–149. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(02)00228-6

Heydari, J., Govindan, K., Nasab H. R. E., & Taleizadeh, (2020). Coordination by quantity flexibility contract in a two-echelon supply chain system: Effect of outsourcing decisions. International Journal Production Economics, 225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107586

Hill, R. M., & Omar, M. (2006). Another look at the single-vendor single-buyer integrated production-inventory problem. International Journal of Production Research, 44(4), 791–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540500334285

Holweg, M., & Pil, F. (2008). Theoretical perspectives on the coordination of supply chains. Journal of Operations Management, 26(3), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.08.003

Huang, F. Y., He, J., & Lei, Q. (2020). Coordination in a retailer-dominated supply chain with a risk-averse manufacturer under marketing dependency. International Transactions in Operational Research, 27(6), 3056–3078. https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.12520

Johnston A., Kavali, A., & Neuhoff, K. (2008). Take-or-pay contracts for renewables deployment. Energy Policy, 36(7), 2481–2503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.02.017

Khan, M. D., Schaefer, D., & Milisavljevic-Syed, J. (2022). Supply chain management 4.0. Looking backward, looking forward, Procedia CIRP, 107, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2022.04.002

Kraljic, P. (1983). Purchasing must become supply management. Harvard Business Review, 61(5), 109–117.

Langley, C. J. Jr., Allen, G. R., & Dale, T. A. (2016). Third party logistics, Latin Amerika Logistics Center.

Larsen, S. T. (2000). European logistics beyond 2000. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistic Management, 30(6), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030010336144

Li, J., Luo, X., Wang, Q., & Zhou, W. (2021). Supply chain coordination through capacity reservation contract and quantity flexibility contract. Omega, 99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2020.102195

Li, X., Lian, Z., Choong, K. K., & Liu, X. (2016). A quantity-flexibility contract with coordination. International Journal Production Economics, 179, 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.06.016

Li, Z. P., Wang, J. J., Perera, S., & Shi, J. (2022). Coordination of a supply chain with Nash bargaining fairness concerns. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2022.102627

Manzhynksi, S., & BIedenbach, G. (2023). The knotted paradox of coopetition for sustainability: Investigating the interplay between core paradox properties. Industrial Marketing Management, 110, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.02.013

Mastos, T. D., Nizamis, A., Terzi, S., Gkortzis, D., Papdopoulos, A., Tsagkalidis, N., Ioannidis, D., Votis, K., & Tzovaras, D. (2021). Introducing an application of an industry 4.0 solution for circular supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126886

Michalski, M., Montes J. L., & Narasimhan, R. (2019). Relational asymmetry, trust, and innovation in supply chain management: a non-linear approach. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(1), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-01-2018-0011

Narus, J. A., & Anderson, J. C. (1996). Rethinking distribution: Adaptive channels. Harvard Business Review, 74(4), 112–120.

Paluri, R. A., & Mishal, A. (2020). Trust and commitment in supply chain management: a systematic review of literature. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(10), 2831–2862. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2019-0517

Ponte, B., Puche, J., Rosillo, R., & de la Fuente, D. (2020). The effects of quantity discounts on supply chain performance: Looking through the Bullwhip lens. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.102094

Sahay, B. S. (2003). Understanding trust in supply chain management relationships. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 103(8), 553–563. http://doi.org/10.1108/02635570310497602

Samper, M. G., Florez, D. G., Borre, J. R., & Ramirez J. (2022). Industry 4.0 for sustainable supply chain management: Drivers and barriers. Procedia Computer Science, 203, 644–650. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.07.094

Sindi, S., & Roe, M. (2017). The evolution of supply chains and logistics. In Strategic Supply Chain Management, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham (pp. 7–25). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54843-2_2

Singh, R. K. (2011). Developing the framework for coordination in supply chain of SMEs. Business Process Management Journal, 17(4), 619–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637151111149456

Singh, R. K., & Benyoucef, L. (2013). A consensus based group decision making methodology for strategic selection problems of supply chain coordination. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 26, 122–134.

Stamatiou, D. R., Kirytopoulos, K. A., Ponis, S. T., Gayialis, S., & Tatsiopoulos, I. (2019). A process reference model for claims management in construction supply chains: the contractors’ perspective. International Journal of Construction Management, 19(5), 382–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2018.1452100

Tantiwattanakul, P., & Dumrongsiri, A. (2019). Supply chain coordination using wholesale prices with multiple products, multiple repiods, and multiple retailers: Bi-level optimization approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 131, 391–407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.03.050

Tejpal, G., Garg, R. K., & Anish, S. (2013). Trust among supply chain partners: a review. Measuring Business Excellence, 17(1), 51–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13683041311311365

Tilson, V. (2008). Monotonicity properties of wholesale price contracts. Mathematical Social Sciences, 56(1), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2008.01.002

Uca, N., Civelek, M. E., & Cemberci, M. (2017). The effect of trust in supply chain on the firm performance through supply chain collaboration and collaborative advantage. Journal of Administrative Sciences, 15(30), 215–230. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3337564

Um, K. H., & Kim, S. M. (2019). The effects of supply chain collaboration on performance and transaction cost advantage: the moderation and nonlinear effects of governance mechanisms. International Journal of Production Economics, 217, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.03.025

Vipin, B., & Amit, R. K. (2021). Wholesale price versus buyback: A comparison of contracts in a supply chain with a behavioral retailer. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 162(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2021.107689

Wang, X., & Disney, S. M. (2016). The bullwhip effect: Progress, trends and directions. European Journal of Operation Research, 250(3), 691–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.07.022

Wang, X., Wang, X., & Su, Y. (2013). Wholesale-price contract of supply chain with information gathering. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 37(6), 3848–3860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2012.07.007

Witkowski, K. (2017). Internet of Things, Big Data, Industry 4.0 – Innovative solutions in logistics and supply chains management. Procedia Engineering, 182, 763–769. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.03.197

Xue, J., Zhang, W., Rasool, Z., & Zhou, J. (2022). A review of supply chain coordination management based on bibliometric data. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 61(12), 10837–10850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2022.04.013

Yao, F., Parilina, E., Zaccour, G., & Gao, H. (2022): Accounting for consumers’ environmental concern in supply chain contracts. European Journal of Operational Research, 301(3), 987–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2021.11.039

Yin, X. (2021). Measuring the bullwhip effect with market competition among retailers: A simulation study. Computers & Operations Research, 132(2), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2021.105341

Download Count : 61

Visit Count : 120

Keywords

Supply Chain Management; Supply Chain Coordination; Contracts

How to cite this article:

Faludi, T. (2024). Supporting cooperation between supply chain members through a combination of soft and hard coordination tools. European Journal of Studies in Management and Business, 31, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32038/mbrq.2024.31.01

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interests

No, there are no conflicting interests.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/