Original Research

Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans: Institutional Barriers, Digital Transformation, and Pathways to Inclusive Growth

- Abstract

- Full text

- Metrics

Women’s entrepreneurship is a critical driver of inclusive growth and innovation, yet women in the Western Balkans continue to face persistent socio-economic, institutional, and digital barriers. This study examines the key determinants shaping women’s entrepreneurial participation in the region through a comparative analysis of secondary data from the World Bank, EBRD, Eurostat, and OECD. Guided by the Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View, the findings reveal substantial gaps in financial inclusion, digital competencies, and institutional support that constrain women’s ability to start and scale businesses. While Albania and Serbia exhibit relatively higher levels of female entrepreneurial engagement, countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and North Macedonia face pronounced digital divides and institutional inefficiencies. The paper concludes with policy recommendations aimed at expanding women’s access to finance, strengthening digital-skills development, and promoting gender-responsive institutional frameworks to build a more inclusive and resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem in the Western Balkans.

Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans: Institutional Barriers, Digital Transformation, and Pathways to Inclusive Growth

Blerta Abazi Chaushi*, Teuta Veseli-Kurtishi, Agron Chaushi

Faculty of Business and Economics, South East European University, Tetovo, North Macedonia

ABSTRACT

Women’s entrepreneurship is a critical driver of inclusive growth and innovation, yet women in the Western Balkans continue to face persistent socio-economic, institutional, and digital barriers. This study examines the key determinants shaping women’s entrepreneurial participation in the region through a comparative analysis of secondary data from the World Bank, EBRD, Eurostat, and OECD. Guided by the Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View, the findings reveal substantial gaps in financial inclusion, digital competencies, and institutional support that constrain women’s ability to start and scale businesses. While Albania and Serbia exhibit relatively higher levels of female entrepreneurial engagement, countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and North Macedonia face pronounced digital divides and institutional inefficiencies. The paper concludes with policy recommendations aimed at expanding women’s access to finance, strengthening digital-skills development, and promoting gender-responsive institutional frameworks to build a more inclusive and resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem in the Western Balkans.

KEYWORDS: Women’s Entrepreneurship, Western Balkans, Institutional Barriers, Financial Inclusion, Digital Skills, Gender Equality, Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Entrepreneurship serves as a cornerstone of economic transformation and social innovation, particularly in small and open economies such as those in the Western Balkans. Yet women remain significantly underrepresented among entrepreneurs due to enduring structural and institutional asymmetries. As these economies transition toward market orientation, gendered differences in financial inclusion, regulatory access, and socio-cultural expectations persist. Despite progress in legal equality and educational attainment, systemic barriers continue to constrain women’s entrepreneurial capacity and limit their contribution to inclusive growth in the region (EBRD, 2024; World Bank, 2025).

Prior studies emphasize a constellation of constraints that collectively impede women’s entrepreneurship, including limited financing channels, complex regulatory procedures, and persistent social norms. Digitalization introduces a further paradox: while it opens new market and networking possibilities, it also magnifies divides in digital skills and technological access. Bridging these divides is essential for equitable participation in emerging digital economies and for ensuring that digital transformation does not reproduce existing gender gaps (EU Commission, 2024; OECD, 2021, 2023).

Although scholarship on gender and entrepreneurship in transition economies is expanding, there is still limited integrative evidence on how socio-economic, institutional, and digital dimensions jointly shape women’s entrepreneurial trajectories in the Western Balkans. This paper addresses that gap by examining regional patterns of women’s economic participation, business ownership, financial inclusion, and digital readiness through a comparative secondary-data analysis. Guided by this objective, the study focuses on three questions: (1) Which institutional and socio-economic barriers most restrict women’s entrepreneurial agency in the Western Balkans? (2) How does digital transformation reshape opportunity structures for women entrepreneurs? (3) What policy measures can strengthen gender-inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystems in the region?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature on women’s entrepreneurship in transition economies, with a focus on socio-economic, institutional, and digital dynamics. Section 3 outlines the research design and secondary data sources used in the analysis. Section 4 presents the main findings on key barriers and enablers of women’s entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans, including financial access, institutional support, and digital readiness. Section 5 discusses policy implications and recommendations for fostering gender-inclusive and digitally empowered entrepreneurial ecosystems, while Section 6 concludes with key insights and directions for future research.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

This study draws on Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory (Ajzen, 1991) and the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991) to understand the socio-economic barriers women entrepreneurs face in the Western Balkans. Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory posits that entrepreneurial behavior is shaped by attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms, which is particularly relevant in a regional context where socio-cultural norms, gender roles, and institutional constraints strongly influence women’s motivation and perceived ability to pursue entrepreneurship (Shinnar et al., 2018). Together, these theoretical lenses help explain how intentions and contextual factors jointly shape women’s entrepreneurial engagement.

The Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991) complements this perspective by emphasizing that entrepreneurial success depends on access to valuable and hard-to-imitate resources. This framework is particularly relevant to the Western Balkans, where women often face structural barriers to financial capital, professional networks, and mentorship (McAdam et al., 2019). By linking Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory with the RBV (Acs et al., 2008; Minniti & Naudé, 2010), this study is able to explore both the socio-cultural factors shaping women’s intentions and the resource constraints that limit their entrepreneurial outcomes, directly informing RQ1 on the core socio-economic and institutional barriers.

Linking Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory to regional gender dynamics clarifies how social norms and institutional rigidity influence women’s motivation to initiate enterprises (Ratten & Braga, 2024). This framework supports RQ1 by connecting attitudinal factors to structural conditions that either stimulate or discourage entrepreneurial entry. The Resource-Based View (RBV) also provides a critical lens for understanding the barriers women face in accessing key resources such as capital, networks, and mentorship. According to the RBV, these resource constraints limit women’s competitive advantage and ability to scale their businesses. This framework is particularly relevant to RQ2: How has digital transformation influenced women's entrepreneurship in the region? As women gain access to digital tools, they may gain resources that were previously inaccessible.

The theoretical insights drawn from Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View provide a lens through which to examine the challenges women entrepreneurs face in the Western Balkans. These barriers are not only socio-cultural but are deeply intertwined with institutional voids and digital access gaps, which will be explored in the following section.

Together, Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View provide complementary lenses for understanding women’s entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans. Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory helps explain how gender norms, perceived behavioral control, and social expectations influence women’s motivation and decision to pursue entrepreneurial activity. The RBV, on the other hand, clarifies how disparities in access to financial, social, and digital resources restrict women’s ability to sustain and grow their ventures. These frameworks jointly illuminate how socio-cultural constraints, institutional voids, and unequal access to resources shape women’s entrepreneurial behavior in the region, guiding the study’s focus on socio-economic barriers and the role of digital transformation.

Women’s Entrepreneurship in Transition Economies

Women’s entrepreneurship in transition economies develops within complex institutional and socio-cultural environments shaped by decades of socialist governance and the rapid shift toward market-oriented economic structures. In the Western Balkans, this transformation has expanded opportunities for private enterprise but has also reproduced gendered disparities in access to resources, visibility, and institutional support (OECD, 2021, 2023; Uvalic, 2024). Market liberalization created space for entrepreneurial activity, yet persistent institutional weaknesses and cultural norms continue to impede women’s participation.

Institutional legacies, including bureaucratic inefficiencies, weak credit markets, and limited enforcement of equality legislation, significantly influence women’s entrepreneurial trajectories across the region. Deep-rooted gender stereotypes and institutional voids limit women’s access to finance, networks, and market opportunities—structural disadvantages that align with the constraints predicted by the Resource-Based View (McAdam et al., 2019; Pergelova et al., 2019). Skepticism toward women’s business leadership further reduces their perceived behavioral control, a core dimension of Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory, thereby discouraging entrepreneurial intentions and risk-taking among women in post-socialist economies.

Intermediary organizations play an increasingly important role in bridging these institutional gaps. Business associations, mentorship networks, and development agencies have sought to strengthen women’s access to training, financial services, and advisory support (Al-Dajani et al., 2015; Ratten & Braga, 2024). Their interventions partially mitigate structural constraints but remain uneven across countries, reflecting the broader fragmentation of institutional support systems in the region.

Digital transformation introduces both opportunities and new layers of inequality. Digital tools can help women bypass traditional market barriers, access broader networks, and reach global markets (Suseno & Abbott, 2021). However, disparities in digital literacy remain a significant obstacle: in several Western Balkan countries, less than 10 percent of women possess above-basic digital skills (EBRD, 2024). This digital divide not only limits the adoption of digital business models but also reinforces pre-existing socio-economic inequalities. As emerging research highlights, targeted investments in digital skills, inclusive financial technologies, and affordable broadband are essential for empowering women to treat digital tools as both strategic resources and competitive capabilities (Ahmed et al., 2025; OECD, 2023).

Understanding women’s entrepreneurship in transition economies, therefore, requires an integrated perspective that connects gender norms, institutional quality, and digital readiness. Gender disparities in entrepreneurship undermine not only individual agency but also regional economic competitiveness, as exclusion from professional networks and capital markets restricts productivity, innovation, and economic diversification (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014; Badghish et al., 2022). These dynamics directly set the foundation for the socio-economic and institutional barriers examined in the following section, where the interaction between financial exclusion, cultural expectations, and limited digital capacity is further unpacked.

Socio-Economic Barriers to Women’s Entrepreneurship

Women entrepreneurs in the Western Balkans face numerous socio-economic barriers that limit their ability to establish and grow businesses. These constraints stem from financial exclusion, cultural expectations, limited access to networks, and institutional biases, which collectively restrict women's entrepreneurial agency (EBRD, 2024; UNDP, 2023). Access to finance remains a critical barrier, as women frequently face stricter collateral requirements, higher credit rejection rates, and a lack of gender-sensitive financial products (Macanović, 2024). Cultural expectations further reinforce these constraints, with women expected to prioritize domestic responsibilities and caregiving, reducing their time, mobility, and ability to engage in entrepreneurship or professional networks (Feranita et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2021). These socio-cultural and financial limitations also limit participation in business mentorship opportunities, which are vital to entrepreneurial success.

The COVID-19 pandemic further magnified these structural inequalities. Women entrepreneurs experienced heightened pressures to balance household responsibilities and business survival, often scaling back operations or shifting to informal or smaller-scale activities. Although many demonstrated resilience by relying on community networks and previous entrepreneurial experience (Castro & Zermeño, 2020; Modgil et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2023), the crisis underscored the lack of institutional support systems that could help women sustain or expand their businesses during economic shocks. This is compounded by broader regional conditions, including high unemployment, a large informal economy, and persistent gender gaps in labor force participation. Female labor force participation in the WB6 countries remains significantly lower than the EU average, particularly in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where only 42.3% and 40.5% of women, respectively, participate in the labor market (UNDP, 2023). These dynamics limit women’s access to professional networks, decision-making roles, and stable income sources, further inhibiting entrepreneurial engagement.

Structural inequalities extend to unpaid care work, as women across the region shoulder a disproportionate share of household labor, which reduces the time and capacity they can invest in entrepreneurial activities (EBRD, 2024). Young women face additional constraints due to limited access to finance, with only 8% of youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina having access to entrepreneurial funding (Sabia et al., 2021). Economic crises further exacerbate these barriers by increasing financial instability for nascent and women-led ventures (Gradev et al., 2013; Najdanović et al., 2019). Addressing these multi-layered barriers requires policies that improve financial inclusion, reduce collateral requirements, expand microfinance options, and promote gender-sensitive lending (Ashish, 2024; OECD, 2023; Qoriawan & Apriliyanti, 2022). Equally important are cultural transformation efforts, mentorship networks, and supportive institutional frameworks that can help shift societal perceptions of women’s roles and empower women to pursue and grow entrepreneurial ventures (Agrawal, 2018; Badghish et al., 2022; Brush et al., 2019).

Overall, the literature suggests that socio-economic barriers in the Western Balkans operate cumulatively rather than independently. Limited financial access reinforces women’s concentration in low-capital sectors; cultural norms amplify time burdens and reduce participation in professional networks; and institutional inefficiencies discourage formalization and business expansion. These interconnected constraints highlight the need to examine women’s entrepreneurship through a holistic framework that captures how structural, economic, and social factors jointly shape entrepreneurial outcomes.

The Role of Digital Transformation in Fostering Women Entrepreneurship

Digital transformation refers to the integration of digital technologies into business operations and has emerged as a crucial enabler for women entrepreneurs in the Western Balkans. Digital tools expand market access, enhance operational efficiency, and help women overcome traditional geographic, social, and economic constraints (Salamzadeh et al., 2024). Evidence shows that women who adopt digital technologies can reach broader customer bases, enter global markets, and manage business relationships more effectively, which is particularly transformative for those in rural or socially restrictive environments. These opportunities allow women to overcome market limitations and create new pathways for business growth.

Despite these benefits, a significant digital divide persists across the Western Balkans (OECD, 2023). According to the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), perceptions of usefulness and ease of use are central to technology adoption; however, many women lack the digital skills necessary to engage effectively with new technologies. Digital entrepreneurship frameworks further emphasize how digital tools reshape opportunity structures (McAdam et al., 2019), yet less than 10% of women in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina possess above-basic digital skills (EBRD, 2024), significantly limiting participation in the digital economy. Rural and low-income women face additional barriers related to infrastructure, training, and access to devices (Kampini et al., 2023; OECD, 2021). These disparities reinforce existing gender inequalities and constrain women’s ability to leverage digital tools for innovation, networking, and business expansion (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014).

International experiences demonstrate that targeted digital literacy programs can significantly strengthen women’s entrepreneurial capacity. Equipping women with practical digital skills enables them to adopt new technologies, enter global value chains, and develop innovative business models (EBRD, 2024; OECD, 2023). Rwanda’s digital upskilling initiatives have increased women’s participation in technology-driven sectors (Celestin, 2024), while Chile’s digital inclusion programs have empowered rural women to establish online businesses through subsidized internet access and free training (Garda, 2021). Estonia’s digital mentorship and entrepreneurial education programs also show how structured support can accelerate women’s digital entrepreneurship (Ashish, 2024; Lall et al., 2023; Mets & Vettik-Leemet, 2024). Similar interventions could help close the gender digital divide in the Western Balkans. As noted by Ratten and Braga (2024), digital tools enable women entrepreneurs to innovate, diversify offerings, and compete globally (Ratten & Braga, 2024). Understanding how digital transformation intersects with socio-cultural and institutional barriers is therefore essential for designing targeted policies that promote inclusive, resilient, and competitive entrepreneurial ecosystems in the region.

In the context of the Western Balkans, these insights illustrate how digital transformation can either mitigate or magnify existing gender disparities. Low levels of digital literacy, uneven access to infrastructure, and limited exposure to digital business tools intersect with long-standing socio-economic constraints, creating additional layers of exclusion for women entrepreneurs. As such, digital transformation should be viewed not only as a technological shift but as a structural condition that directly influences women’s entrepreneurial agency in the region.

Method

This study adopts a descriptive and comparative research design based on the analysis of secondary quantitative and qualitative data. The methodological approach aims to identify structural patterns, regional disparities, and contextual factors that affect women’s entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans (WB6): Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. The research design aligns with the study’s objective of examining how socio-economic, institutional, and digital factors jointly shape women’s entrepreneurial opportunities in transition economies.

Research Design

A comparative cross-country design was used to evaluate variations in entrepreneurial participation, financial inclusion, digital literacy, and labor market conditions across WB6. This approach allows for a systematic examination of similarities and differences across countries while identifying structural determinants of women’s entrepreneurship in the region. Descriptive analysis was selected because the study aims to map existing conditions rather than test causal hypotheses.

Data Sources

The study relies exclusively on high-quality institutional secondary data from internationally recognized sources, including:

· World Bank Gender Data Portal (entrepreneurship, ownership, financial inclusion, regulatory indicators)

· European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD, 2024) (Women in Business Program, digital skills, institutional quality)

· Eurostat (2023–2024) (labor force participation, gender gaps, economic structure)

· UNDP (2023) Human Development Reports (employment, youth inclusion, informal economy)

· OECD (2021–2023) (digital readiness, digital literacy gaps, technology adoption)

· National statistical offices of WB6 countries

· Regional Cooperation Council (2021) (digital skills gap data)

These datasets were selected for their methodological consistency, regional comparability, and annual reporting structures, ensuring reliability for comparative analysis.

Variables and Indicators

Across datasets, the following indicators were extracted and synthesized:

· Entrepreneurship Indicators: women-owned businesses, self-employment rates

· Labor Market Indicators: female labor force participation, unemployment rates

· Financial Inclusion Indicators: access to credit, collateral requirements, entrepreneurship financing

· Institutional Indicators: business environment, regulatory burden, access to networks

· Digital Indicators: basic and above-basic digital skills, digital literacy, ICT access

These indicators were chosen for their relevance to the research questions and consistent reporting across countries.

Data Analysis Procedure

Data were analyzed through a combination of descriptive statistical comparisons, including percentages, rankings, and cross-country contrasts, complemented by a thematic synthesis of institutional reports to contextualize quantitative findings. A theory-driven interpretation was applied, drawing on the Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View to explain observed regional patterns and barriers. Tables and figures were produced to illustrate variations in women’s entrepreneurship, digital skills, and economic participation across the Western Balkans. In addition, qualitative institutional reports were systematically reviewed and coded to identify recurring themes related to institutional constraints, financial barriers, and digital divides, enabling a comprehensive and integrated understanding of the factors shaping women’s entrepreneurial outcomes in the region.

Methodological Limitations

Because the study relies on secondary data, the analysis is limited by:

· Variability in reporting years across WB6 statistical offices

· Lack of micro-level data specific to women-led firms

· Inability to infer causal relationships

Despite these limitations, the use of validated international datasets ensures comparability and robustness in addressing the study’s research questions.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the findings of the study and interprets them in relation to existing literature and the theoretical lenses outlined earlier. Relying on secondary data and institutional reports from the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Eurostat, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for the period 2014–2024, the analysis adopts a comparative and descriptive approach. Socio-economic indicators, digital-readiness measures, and gender-disaggregated entrepreneurship metrics are synthesized to highlight structural patterns across the Western Balkans. By integrating evidence from regional and global sources, the findings reveal how institutional constraints, socio-economic disparities, and digital divides jointly shape women’s entrepreneurial participation in the WB7. The discussion further interprets these results through the Resource-Based View and the Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory, identifying key determinants of women’s entrepreneurial behavior and outlining policy directions to foster more inclusive and resilient entrepreneurial ecosystems in the region.

Findings on Gender Disparities in Business Ownership

Using indicators extracted from national statistical offices, this subsection examines gender disparities in labor-force participation, business ownership, and earnings across the Western Balkans. As shown in Table 1, substantial variation exists among the WB6 economies, reflecting persistent structural and cultural asymmetries that shape women’s participation in economic and entrepreneurial activities.

Key Socioeconomic Indicators for Women in WB6 (2023)

|

Country |

Female Labor Force Participation (%) |

Women-Owned Businesses (%) |

Gender Pay Gap (%) |

|

Albania |

52.8 |

30 |

21.1 |

|

Kosovo |

42.3 |

18 |

28.5 |

|

North Macedonia |

42.8 |

29 |

19.4 |

|

Serbia |

50.9 |

31.7 |

16.8 |

|

Bosnia and Hercegovina |

40.5 |

28 |

33 |

|

Montenegro |

49.4 |

23.7 |

16 |

Source: Derived from national state statistical offices for each country

These figures reveal pronounced cross-country differences in women’s economic engagement. Kosovo records the lowest female labor-force participation (42.3 percent) and women-owned businesses (18 percent), pointing to significant institutional and cultural constraints. By contrast, Serbia and Albania demonstrate comparatively higher rates of participation and business ownership, suggesting more supportive institutional environments. These disparities mirror broader dynamics in the region, where institutional voids, cultural norms, and unequal access to resources continue to limit women’s entrepreneurial opportunities.

Interpreted through Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory (Ajzen, 1991), these outcomes indicate that subjective norms and perceived behavioral control strongly influence women’s likelihood of pursuing entrepreneurship. In societies where patriarchal expectations remain prominent, women face greater psychological and structural disincentives to engage in business activity. From the perspective of the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), unequal access to capital, networks, and mentorship restricts women’s ability to build and deploy the strategic resources necessary to sustain business growth and competitiveness.

The gender pay gap reinforces these findings. Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina report gaps exceeding 25 percent, reflecting persistent labor-market inequalities that spill over into entrepreneurial activity by reducing women’s savings capacity, investment potential, and creditworthiness. These patterns collectively demonstrate that women’s entrepreneurial outcomes in the Western Balkans are shaped not only by individual ambition but by broader socio-cultural and institutional contexts.

Addressing these disparities requires integrated reforms that combine gender-responsive financial systems, stronger institutional guarantees for equal pay and parental leave, and targeted digital-skills programs to broaden women’s entrepreneurial capabilities. The next subsection explores how digital transformation can reduce some of these barriers and expand women’s opportunities to participate in regional entrepreneurship.

Findings about Financial and Institutional Barriers

Women entrepreneurs across the Western Balkans continue to face substantial financial and institutional constraints that limit their ability to launch, sustain, and scale business ventures. Evidence indicates that banks and other financial institutions frequently impose stricter collateral and credit-history requirements on women than on men, resulting in reduced access to formal financing and growth capital. These financial disparities are compounded by bureaucratic inefficiencies, which make business registration, licensing, and regulatory compliance more time-consuming and costly for women-led firms.

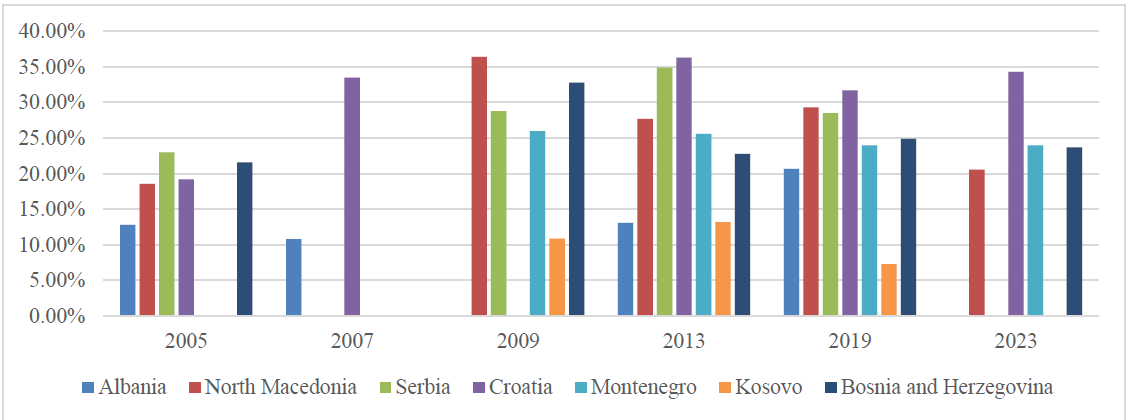

Firms with Female Participation in Ownership

Source: Adapted from (World Bank, n.d.)

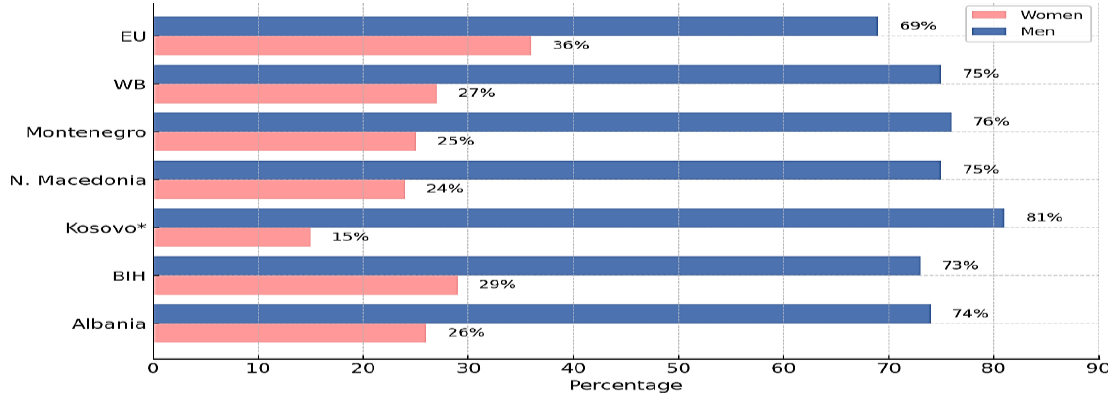

Figure 1 illustrates the limited representation of women in firm ownership across the region, signaling persistent structural barriers in the formal business sector. Complementing this, Figure 2 shows comparatively higher rates of female self-employment, suggesting that many women pursue entrepreneurial activity out of necessity rather than opportunity. Together, these patterns reveal a structural duality: women remain underrepresented in formal business ownership while being disproportionately concentrated in informal or small-scale self-employment. This duality is directly linked to financial exclusion and institutional weaknesses that constrain women’s entrepreneurial pathways.

Self-employment in Western Balkans

Source: Adapted from (UNDP, 2023)

Across the WB6, three major challenges emerge:

1. Access to Finance: Women entrepreneurs continue to face disproportionate collateral requirements, reduced credit access, and limited eligibility for larger-scale investment instruments, constraining their ability to expand or formalize their businesses.

2. Regulatory Barriers: Administrative complexity, inconsistent law enforcement, and outdated business-registration procedures discourage formalization and impede the growth of women-led enterprises.

3. Sectoral Concentration: Women remain disproportionately represented in lower-margin sectors such as retail, services, and agriculture—industries that typically attract smaller funding opportunities and yield limited profitability.

Interpreted through the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), these constraints undermine women’s ability to access and deploy essential tangible and intangible assets, including capital, networks, and market knowledge, that are foundational for establishing and sustaining competitive advantage. At the same time, Institutional Theory (North, 1990) emphasizes that regulatory inefficiencies and weak institutional enforcement reproduce gendered patterns of exclusion from formal markets, further entrenching inequalities in resource access.

Despite ongoing support from the European Union, the EBRD, and national development agencies, gender gaps in financial inclusion remain deeply rooted. To promote equitable access, financial systems in the Western Balkans must adopt gender-sensitive credit assessments, expand microfinance and guarantee schemes, and incentivize the adoption of digital-finance tools among women entrepreneurs. Such interventions would strengthen women’s resource base, support business scalability, and contribute to broader EU and regional objectives for inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

The Role of Support Programs

International, regional, and national support programs have become essential mechanisms for alleviating the financial and institutional barriers faced by women entrepreneurs across the Western Balkans. At the regional level, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has channeled more than €100 million through its Women in Business Program, expanding women’s access to finance, advisory services, and capacity-building initiatives (EBRD, 2024). Similarly, the European Union’s EU for Gender Equality in the Western Balkans initiative has mobilized substantial resources to promote equal opportunities and support women-led enterprises (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2023)

At the national level, several targeted interventions have emerged, albeit with varying degrees of effectiveness. In North Macedonia, the Women’s Entrepreneurship Support Platform has provided training and financing to more than 1,000 women (NPWE, n.d.), while in Serbia, ProCredit Bank offers tailored loan schemes with favorable terms for women-led small and medium enterprises (ProCredit Bank, 2025). Civil society organizations also play an important complementary role. Groups such as the Kosovo Women’s Network and the Albania Women’s Empowerment Fund provide grants, mentorship, advocacy, and gender-sensitive support services, helping women navigate financial and institutional barriers (Albania Investment Development Agency, 2023; Kosovo Women’s Network, 2024).

Despite these efforts, substantial financing gaps persist. Women in the region continue to receive between 10 and 30 percent less funding than men and remain concentrated in lower-margin sectors such as retail, services, and agriculture (World Bank, n.d.). The uneven effectiveness of support programs across countries largely reflects variations in institutional commitment, fragmented funding mechanisms, and limited monitoring of program outcomes. Viewed from the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), these initiatives partially address constraints on women’s access to financial, human, and social capital. However, from the perspective of Institutional Theory, their long-term impact depends on governments’ ability to institutionalize gender-responsive financing frameworks and embed these initiatives within broader socio-economic policies.

While support programs offer valuable resources and opportunities, their fragmented implementation and inconsistent institutional backing limit their capacity to produce structural, long-term improvements in women’s entrepreneurial participation. Strengthening coordination among financial institutions, development agencies, and national governments is therefore essential to ensure that these programs evolve from short-term interventions into durable enablers of gender-inclusive economic development.

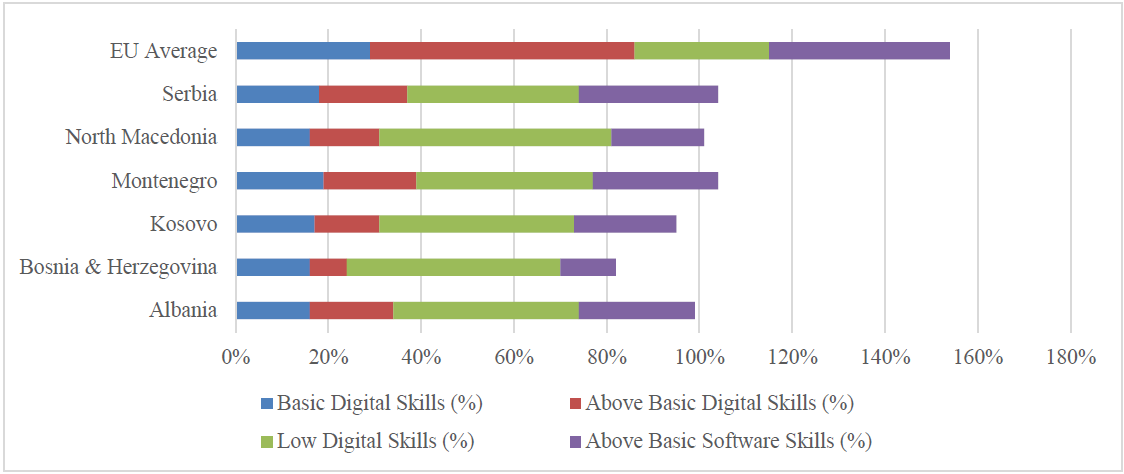

Findings on Digital Literacy and Entrepreneurship

Table 2 presents key indicators of digital literacy across the Western Balkans, revealing a substantial skills gap compared with the European Union average. No WB6 country surpasses 20 percent in above-basic digital skills, whereas the EU average stands at 57 percent. North Macedonia (50 percent) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (46 percent) record the highest proportions of individuals with low digital proficiency, underscoring significant barriers to participation in the digital economy. Even Serbia and Montenegro, countries with relatively higher digital readiness, remain well below EU benchmarks.

Table 2

Digital Literacy Gap in the Western Balkans

|

Country |

Basic Digital Skills (%) |

Above Basic Digital Skills (%) |

Low Digital Skills (%) |

Above Basic Software Skills (%) |

|

Albania |

16% |

18% |

40% |

25% |

|

Bosnia & Herzegovina |

16% |

8% |

46% |

12% |

|

Kosovo |

17% |

14% |

42% |

22% |

|

Montenegro |

19% |

20% |

38% |

27% |

|

North Macedonia |

16% |

15% |

50% |

20% |

|

Serbia |

18% |

19% |

37% |

30% |

|

EU Average |

29% |

57% |

29% |

39% |

Source: Derived from the report on digital skills need and gap (Regional Cooperation Council, 2021)

The data clearly illustrate that digital literacy remains a critical constraint for entrepreneurship in the region. Digital proficiency is increasingly central to entrepreneurial success, enabling firms to expand market access, improve efficiency, and adopt innovative business models. According to the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), individuals' adoption of technology is strongly influenced by their perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. Persistent digital skill shortages, combined with limited ICT infrastructure, reduce women entrepreneurs’ confidence in adopting digital tools such as online payments, e-commerce platforms, and digital marketing systems. As a consequence, many women remain excluded from the fastest-growing segments of the regional economy.

Figure 3 visually complements the data reported in Table 2 by translating the observed digital literacy gaps into a clear cross-country comparison. It highlights that all Western Balkan economies lag substantially behind the EU average, particularly with respect to above-basic digital skills, while low digital proficiency remains widespread across the region. The figure also makes apparent the internal variation among WB6 countries, with North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina exhibiting especially high shares of individuals with low digital skills, and Serbia and Montenegro performing comparatively better, though still well below EU benchmarks. By visually reinforcing the tabular findings, the figure helps clarify both the scale and persistence of the digital skills gap prior to the discussion of its implications for entrepreneurship.

Digital Literacy Gap in the Western Balkans (2023)

Source: Adapted from (Regional Cooperation Council, 2021)

The findings also highlight substantial potential gains from improving digital competencies. Enhancing women’s skills in software use, digital marketing, and online finance can expand their entrepreneurial opportunities and improve competitiveness. Evidence from Estonia, Chile, and Rwanda demonstrates that targeted digital-skills programs can significantly advance women’s entrepreneurial capabilities and participation in the digital economy (Celestin, 2024; Garda, 2021; Mets & Vettik-Leemet, 2024).

Closing the digital literacy gap requires coordinated regional strategies aligned with EU standards. Large-scale programs led by universities, innovation hubs, incubators, and industry associations can provide the necessary training frameworks. Strengthening women’s digital capabilities would not only increase their entrepreneurial competitiveness but also contribute to broader goals of digital transformation and inclusive growth in the Western Balkans.

Overall, the patterns observed reinforce that digital exclusion amplifies existing socio-economic inequalities. Consistent with the Technology Acceptance Model, women with lower digital skills perceive digital technologies as less accessible and less useful, reducing their likelihood of adopting tools essential for modern entrepreneurship.

Findings about Gender Inequality in Economic Participation

Gender disparities continue to shape economic participation and labor-market dynamics across the Western Balkans, limiting women’s employment opportunities, financial autonomy, and access to leadership positions. Structural constraints, including unequal access to finance, weak institutional enforcement, and persistent social norms, interact with cultural expectations surrounding unpaid care work and low representation in STEM fields to reinforce gendered inequalities. While Serbia and Montenegro have shown gradual improvements, countries such as Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, and North Macedonia continue to experience some of the widest gender gaps in the region.

Table 3

Gender Gaps in Employment, Finance, and Social Inclusion in the Western Balkans

|

Category |

Key Insights |

Country Comparisons |

Implications |

|

Labor Force Participation and Employment |

Female labor force participation remains low, with significant gender gaps in access to employment and leadership roles. |

According to EBRD Assessment of Transition Qualities (ATQ): |

- Limits economic growth and productivity. |

|

Financial Inclusion and Economic Participation |

Women face significant barriers in accessing credit, investment, and financial services, leading to lower business ownership and economic independence. |

- High financial inclusion gaps: Bosnia & Herzegovina, North Macedonia. |

- Hinders business growth and innovation. |

|

Gender Representation in Decision-Making Roles |

Women remain underrepresented in leadership positions, with slow progress in political participation. |

- Lowest representation in managerial roles: Bosnia & Herzegovina, Albania, North Macedonia. |

- Less diverse leadership impacts policy and business decisions. |

|

Digital and STEM Participation |

Women are underrepresented in STEM education and digital skills training, affecting future job prospects in high-paying sectors. |

- Largest digital gender divide: Albania, Kosovo. |

- Limits women’s access to high-income tech jobs. |

|

Unpaid Care Work |

Women perform significantly more unpaid domestic and care work, limiting their time for education, work, and entrepreneurship. |

- Highest burden: Albania (women spend 5+ hours daily on unpaid domestic work, men spend far less). |

- Reduces women’s participation in the workforce. |

|

Social Norms and Gender Discrimination |

Deeply ingrained social norms reinforce traditional gender roles, restricting women's financial independence and property rights. |

- Strongest barriers: Kosovo, Albania (women face inheritance and financial restrictions). |

- Limits the economic empowerment and social mobility. |

Source: Authors own (based on Macanović's (2024) publication)

The indicators in Table 3 demonstrate that gender inequality in the Western Balkans is multidimensional, encompassing labor-force participation, financial inclusion, leadership representation, STEM engagement, unpaid care responsibilities, and discriminatory social norms. From the perspective of Institutional Theory, many of these disparities persist because equality legislation is weakly enforced, gender mainstreaming remains limited, and institutional arrangements fail to provide adequate incentives or protections for women’s economic participation. Low representation in decision-making roles, for example, reflects institutional barriers that restrict women’s influence over policy and organizational processes, perpetuating unequal outcomes.

At the same time, Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory (Ajzen, 1991) helps explain how internalized social norms and perceived behavioral constraints diminish women’s motivation and confidence to engage in entrepreneurship. High burdens of unpaid care work, particularly pronounced in Albania, Kosovo, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, further reduce the time and flexibility women need for business development, formal employment, or skills upgrading. These factors collectively suppress women’s entrepreneurial intentions, reinforcing labor-market segmentation and lower economic participation.

Financial inclusion gaps and limited participation in digital and STEM-driven sectors further constrain women’s entry into high-growth industries. Women’s underrepresentation in digital-economy initiatives, coupled with low digital skills in several countries, restricts access to technology-enabled entrepreneurial opportunities. These structural disadvantages echo the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991), which emphasizes that restricted access to financial, human, and social capital undermines women’s ability to acquire and leverage the strategic resources required for business growth.

Addressing these entrenched inequalities requires a multi-layered policy approach. Priority actions include: (1) enforcing gender-responsive legislation and strengthening institutional support mechanisms; (2) expanding women’s participation in STEM education and digital-entrepreneurship initiatives; (3) investing in childcare and eldercare infrastructure to reduce the unpaid care burden; and (4) ensuring equitable access to financial services, leadership opportunities, and entrepreneurship programs. Such measures are essential for fostering inclusive economic growth and enabling women to fully contribute to the region’s social and economic transformation. Collectively, the identified inequalities constrain both the motivational drivers highlighted by Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the resource accessibility emphasized by the RBV, making them core structural barriers to women’s entrepreneurial participation.

Discussion: Policy Implications and Recommendations

The findings reveal that socio-economic, institutional, and digital barriers in the Western Balkans operate cumulatively rather than independently. Interpreted through the Resource-Based View (RBV), these constraints represent systematic disadvantages in access to financial, human, and social capital that undermine women’s ability to acquire and deploy strategic resources for entrepreneurial competitiveness. At the same time, Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory (EIT) highlights how cultural norms, institutional expectations, and perceived behavioral control shape women’s motivation and confidence to engage in entrepreneurial activity. Together, these theories illustrate that women’s entrepreneurial outcomes are shaped by the interplay of structural contexts and individual-level perceptions.

Persistent gender disparities continue to limit women’s entrepreneurial potential in the region. Despite signs of progress, unequal financial access, regulatory inefficiencies, socio-cultural constraints, and digital skill gaps remain widespread. Cross-country variations demonstrate that while Albania and Serbia show relatively higher levels of women’s participation, women in Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia face deeper institutional and cultural barriers. Addressing these inequalities requires coordinated, multidimensional policy interventions that combine financial reform, digital capacity building, institutional strengthening, and cultural transformation.

Policy Recommendations

· Strengthen Financial Inclusion: Women entrepreneurs require equitable access to financial capital to start and scale their ventures. Governments and financial institutions should introduce gender-sensitive credit instruments, reduce collateral requirements, and expand microfinance schemes tailored to women-led enterprises. Stronger partnerships among banks, development agencies, and private investors can mobilize venture capital and reduce gender bias in lending processes.

· Bridge the Digital Skills Divide: Closing the digital gender gap is essential for enhancing competitiveness and enabling participation in technology-driven industries. Regional digital-skills programs should prioritize countries with the widest disparities, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and North Macedonia. Initiatives that combine ICT training, subsidized access to digital tools, and targeted STEM scholarships for women can accelerate integration into the digital economy and support digital entrepreneurship.

· Enhance Institutional and Regulatory Support: Simplifying business registration procedures, strengthening property rights, and promoting gender-equitable legal frameworks can encourage women to formalize and expand their enterprises. Establishing one-stop service centers that provide legal support, financial counselling, and mentorship would reduce bureaucratic complexity and build institutional trust among women entrepreneurs.

· Promote Cultural and Social Change: Achieving gender equality in entrepreneurship requires sustained efforts to challenge traditional norms that restrict women’s economic participation. Awareness campaigns, inclusive educational programs, and media initiatives can help shift public perceptions. Increased visibility of successful women entrepreneurs can further contribute to normalizing women’s presence in leadership and business roles.

· Expand Entrepreneurial Networks and Mentorship: Business networks and mentorship programs help women navigate information gaps, build confidence, and gain access to market opportunities. Developing women-focused incubators, accelerators, and peer-learning platforms can foster collaboration and knowledge exchange. Fiscal incentives and grant programs aimed at women-led startups, particularly in underrepresented sectors, can stimulate innovation and job creation.

These policy interventions align closely with the theoretical insights of both EIT and the RBV. Strengthening women’s access to resources, networks, and technology addresses RBV-related constraints, while enhancing skills, visibility, and institutional support improves women’s perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intentions as described by EIT. Together, these measures provide a comprehensive foundation for building an inclusive, resilient, and innovation-oriented entrepreneurial ecosystem across the Western Balkans.

Conclusion

This study examined the socio-economic, institutional, and digital determinants shaping women’s entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans, demonstrating that persistent gender inequalities continue to hinder women’s participation in business formation, growth, and leadership. While Albania and Serbia exhibit comparatively higher levels of engagement, the majority of WB6 countries continue to face entrenched financial barriers, institutional inefficiencies, and significant digital-skills gaps. These challenges are deeply rooted in structural and cultural dynamics that influence women’s entrepreneurial intentions and their access to essential resources.

Drawing on Entrepreneurial Intentions Theory and the Resource-Based View, the findings underscore that women’s entrepreneurial participation depends not only on motivation and perceptual factors but also on access to financial capital, institutional support, and digital capabilities. Addressing these constraints is essential for enabling women to leverage opportunities in both traditional and emerging sectors.

Policy interventions should therefore prioritize the development of gender-responsive financial systems, large-scale digital-skills programs, and simplified regulatory frameworks that encourage business formalization and growth. Investments in childcare infrastructure, mentorship networks, and women-focused incubators can further strengthen entrepreneurial participation and resilience, particularly in underrepresented or high-growth sectors.

Future research should incorporate primary data collection—such as surveys, interviews, and case studies—to validate and extend these findings. Exploring the potential of AI, fintech, and digital platform solutions to enhance women’s access to finance, networks, and markets is a promising avenue for further investigation.

Ultimately, reducing gender disparities in entrepreneurship is both a matter of social equity and a driver of economic transformation. By fostering inclusive financial, institutional, and digital ecosystems, policymakers and development actors can unlock the full potential of women entrepreneurs to contribute to innovation, competitiveness, and sustainable growth across the Western Balkans.

References

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9

Agrawal, R. (2018). Constraints and challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in emerging market economy and the way forward. JWEE, 3–4, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.28934/jwee18.34.pp1-19

Ahmed, H., Bajwa, S. U., Nasir, S., Khan, W., Mahmood, K., & Ishaque, S. (2025). Digital empowerment: Exploring the role of digitalization in enhancing opportunities for women entrepreneurs. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-025-02658-0

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Albania Investment Development Agency. (2023). Albania Women’s Empowerment Fund. https://aida.gov.al

Al-Dajani, H., Carter, S., Shaw, E., & Marlow, S. (2015). Entrepreneurship among the displaced and dispossessed: Exploring the limits of emancipatory entrepreneuring. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 713–730.

Antonio, A., & Tuffley, D. (2014). The gender digital divide in developing countries. Future Internet, 6(4), 673–687.

Ashish, I. (2024). The role of microfinance in empowering women entrepreneurs (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 5024302). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5024302

Badghish, S., Ali, I., Ali, M., Yaqub, M. Z., & Dhir, A. (2022). How socio-cultural transition helps to improve entrepreneurial intentions among women? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(4), 900–928. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-06-2021-0158

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., & Welter, F. (2019). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9992-9

Castro, M. P., & Zermeño, M. G. G. (2020). Being an entrepreneur post-COVID-19–resilience in times of crisis: A systematic literature review. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(4), 721–746.

Celestin, R. P. (2024). Initiatives aimed at increasing the women in the tech industry in Rwanda and their impact on social and economic development. Reviewed Journal of Social Science & Humanities, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.61426/rjssh.v5i1.211

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

EBRD. (2024). Women in Business programme. https://www.ebrd.com/women-in-business/finance-and-advice-for-women-in-business.html

EU Commission. (2024, October 30). Strategy and Reports—Enlargement and Eastern Neighbourhood. https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/strategy-and-reports_en

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2023). Gender Equality Index: Measuring progress in the Western Balkans. https://doi.org/10.2839/852703

Feranita, N. V., Ahmad, A. R., & Hasan, A. R. (2023). Digital entrepreneurship model: Optimizing internal and external support for female entrepreneurs. Integrated Journal of Business and Economics, 7(3), 503–517.

Garda, P. (2021). Making digital transformation work for all in Chile (OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1684; OECD Economics Department Working Papers, Vol. 1684). https://doi.org/10.1787/6b1a524c-en

Gradev, G., Salimović, E., & Sergi, B. (2013). Developments of the economies, macroeconomic indicators and challenges in south-east European countries. SEER: Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Eastern Europe, 251–277.

Kampini, T., Kalepa, J., Mwasinga, K., & others. (2023). Unrealized potential: Female entrepreneurship and the digital gender gap in Sub-Saharan Africa: Development futures series No. 62. UNDP. https://cosdev.univpancasila.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Unrealized-Potential-Female-Entrepreneurship-and-the-Digital-Gender-Gap-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa.pdf

Khan, R. U., Salamzadeh, Y., Shah, S. Z. A., & Hussain, M. (2021). Factors affecting women entrepreneurs’ success: A study of small-and medium-sized enterprises in emerging market of Pakistan. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10, 1–21.

Kosovo Women’s Network. (2024). Kosovo Women’s Fund. Kosovo Women’s Network. https://womensnetwork.org/kosovo-womens-fund/

Lall, S. A., Chen, L.-W., & Mason, D. P. (2023). Digital platforms and entrepreneurial support: A field experiment in online mentoring. Small Business Economics, 61(2), 631–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00704-8

Macanović, V. (2024). Women’s rights in Western Balkans 2024. Femicide Memorial, Autonomous Women’s Center. https://kvinnatillkvinna.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/The-Kvinna-till-Kvinna-Foundation-Womens-Rights-in-Western-Balkans-2024.pdf

McAdam, M., Crowley, C., & Harrison, R. T. (2019). “To boldly go where no [man] has gone before”—Institutional voids and the development of women’s digital entrepreneurship1. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 146, 912–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.051

Mets, T., & Vettik-Leemet, P. (2024). Women in the sustainability new ventures in the digital era: Out from the shadow of the small country male-dominated startup ecosystem. Green Finance, 6(3), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.3934/GF.2024015

Minniti, M., & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 277–293.

Modgil, S., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Gupta, S., & Kamble, S. (2022). Has Covid-19 accelerated opportunities for digital entrepreneurship? An Indian perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121415.

Najdanović, Z., Mladenović, M. Ž., & Tutek, N. (2019). Competitiveness of business environment of the Western Balkan countries. Management International Conference. Https://doi. org/10.26493/978-961-6832-68-7.9.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

NPWE. (n.d.). National Platform for Women EN |. Retrieved February 19, 2025, from https://en.weplatform.mk/

OECD. (2021). Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans: Assessing Opportunities and Constraints. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/4d5cbc2a-en

OECD. (2023, October 10). Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2023. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/economic-convergence-scoreboard-for-the-western-balkans-2023_2f4b0366-en.html

Pergelova, A., Manolova, T., Simeonova-Ganeva, R., & Yordanova, D. (2019). Democratizing entrepreneurship? Digital technologies and the internationalization of female-led SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 14–39.

ProCredit Bank. (2025). Take Your Business to the Next Level | ProCredit Bank. https://www.procreditbank.rs/en/blog/take-your-business-next-level

Qoriawan, T., & Apriliyanti, I. D. (2022). Exploring connections within the technology-based entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) in emerging economies: Understanding the entrepreneurship struggle in the Indonesian EE. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(2), 301–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-02-2021-0079

Ratten, V., & Braga, V. (2024). Internationalization through digital empowerment for women Filigree Jewelry Artisan entrepreneurs in Portugal. Thunderbird International Business Review, 66(5), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22394

Regional Cooperation Council. (2021). Regional Cooperation Council | Digital skills needs and gaps in the Western Balkans—Scope and objectives for a fully-fledged assessment. https://www.rcc.int/pubs/129/digital-skills-needs-and-gaps-in-the-western-balkans--scope-and-objectives-for-a-fully-fledged-assessment

Sabia, L., Bell, R., & Bozward, D. (2021). Crowdfunding and entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans. Entrepreneurial Finance, Innovation and Development, 50–68.

Salamzadeh, A., Dana, L.-P., Ghaffari Feyzabadi, J., Hadizadeh, M., & Eslahi Fatmesari, H. (2024). Digital technology as a disentangling force for women entrepreneurs. World, 5(2), 346–364.

Santos, S. C., Liguori, E. W., & Garvey, E. (2023). How digitalization reinvented entrepreneurial resilience during COVID-19. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, 122398.

Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

Suseno, Y., & Abbott, L. (2021). Women entrepreneurs’ digital social innovation: Linking gender, entrepreneurship, social innovation and information systems. Information Systems Journal, 31(5), 717–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12327

UNDP. (2023). Women in Western Balkan economies in a nutshell. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-01/report_on_women_in_wb_economies_in_a_nutshel_17.02.2023_1.pdf

Uvalic, M. (2024). The potential of the new Growth Plan for the Western Balkans. Cadmus. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/77869

World Bank. (n.d.). Gender Data Portal. World Bank Gender Data Portal. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/home

World Bank. (2025). Western Balkans Regular Economic Report. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eca/publication/western-balkans-regular-economic-report

Download Count : 9

Visit Count : 45

Keywords

Women’s Entrepreneurship; Western Balkans; Institutional Barriers; Financial Inclusion; Digital Skills; Gender Equality; Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

How to cite this article

Chaushi, B. A., Veseli-Kurtishi, T., & Chaushi, A. (2025). Women’s entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans: Institutional barriers, digital transformation, and pathways to inclusive growth. European Journal of Studies in Management and Business, 36, 54-74. https://doi.org/10.32038/mbrq.2025.36.04

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interests

No, there are no conflicting interests.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. You may view a copy of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License here: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/